By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm –

We sometimes meet attorneys who want a low-technology approach in trial. I imagine they see themselves standing in front of the jury saying something like, “well…I’m just a country lawyer and I don’t know much about all these new fangled gadgets – documents flying on the screen, Star Wars animation and whatnot. But I do know one thing…” The thought is that jurors will look at the party using all the technological bells and whistles on their side and think, “well, that is deep pockets and manipulation!” Then they’ll look at the other side, with arguments clothed only in reason and the law, and think “well, that there must be the simple truth!”

But does this David versus Goliath schtick actually work when jurors are comparing two parties with differing reliance on technology in the courtroom? Based on our study, looking at the reactions of 1,375 mock jurors reacting to videorecorded plaintiff and defense arguments, under five different conditions of graphics use, we think that the answer is no. Years ago, when technology was first coming onto the scene, there may have been suspicion of the higher-technology party. But today’s juries are much more used to sophisticated visual strategies because they’re more likely to see them on the news, at school, and on the internet. This post, the third of our five-part series reporting the results of our Visual Persuasion Study, takes a look at the research on juror comparisons between parties, and shares some recommendations on how you should plan to stack up against the other party.

The Persuasion Strategies Visual Persuasion Study

To compare parties’ use of graphics, we took an experimental approach and used one consistent style for a plaintiff’s presentation (using no designed graphics, but a few on-screen documents) and developed five separate versions of the same defense presentation, differing only in the style of visuals used, and tested them out using 1,375 mock jurors. We compared five different approaches to visual persuasion:

1. No graphics

2. Flip chart graphics, created live

3. Static graphics, designed, but not animated

4. Animated graphics

5. Immersion: a mix of static and animated graphics used continuously, so that imagery is shown throughout the presentation

What we found, we’re reporting for the first time in these blog entries (See part one for a more complete description of the study).

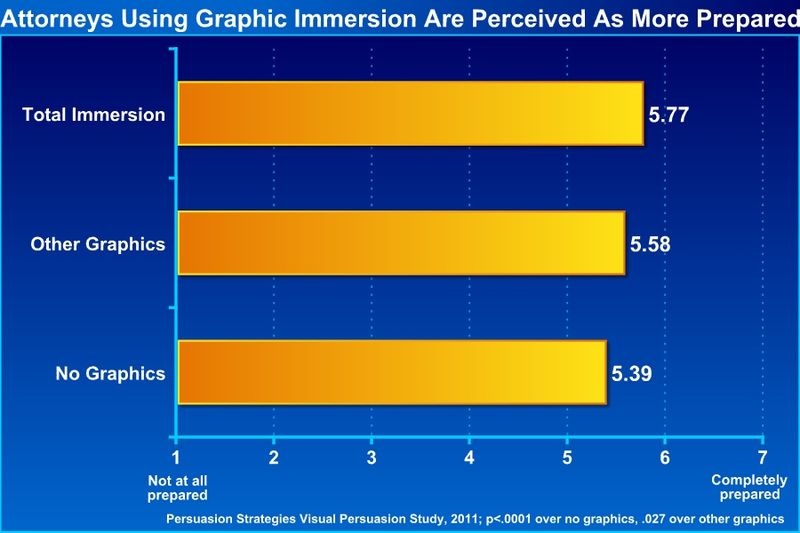

The Perception of Preparedness

Naturally, juries and other audiences look for signs that those addressing them are prepared. That is why it can spell doom to fumble with anything — documents, technology, motions — in front of a jury. From their standpoint, the attitude is, “you are pulling us out of our lives and using our time, so rule one is ‘be prepared.'” One of our main findings is that the party using graphics is perceived as more prepared, particularly when attorneys use immersion approach in which jurors see continuous imagery accompanying a presentation.

(Please click to see full-sized image)

So at a statistically significant level, jurors are likely to see the party using graphics continuously as modestly more prepared than the party who doesn’t.

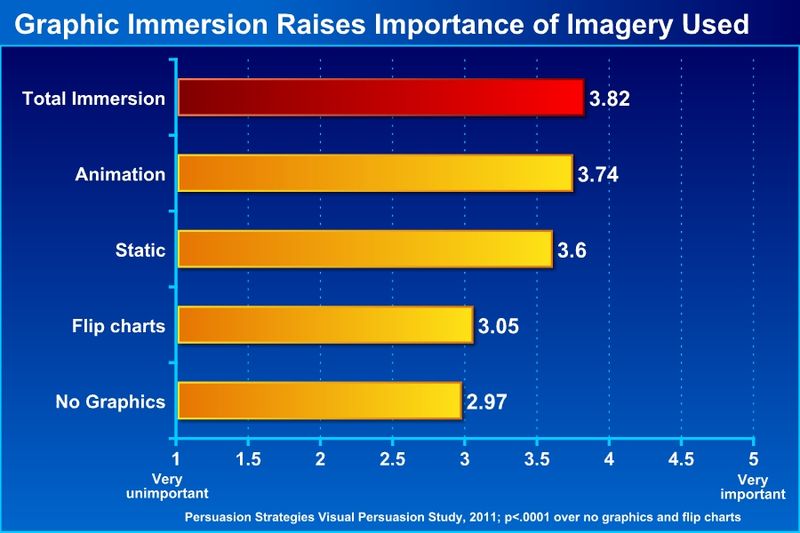

The Percieved Importance of The Presentation

Another interesting finding from the research is the role of graphic style in highlighting the importance of the presentation itself. After viewing the summary arguments, we asked our research participants to rate the importance or unimportance of various issues and features of what they saw. When the defense presentation made greater use of visual tools, mock jurors saw the defense presentation as significantly more important than when the defense didn’t use graphics, or used fewer graphics. More specifically, jurors seeing presentations based on a graphic immersion approach from the defense felt that the imagery used by both parties was significantly more important.

(Please click to see full-sized image)

In other words, instead of seeing jurors distrust and discount the side with greater technoligcal reliance, we found the opposite: If one side is using visuals, then the case is more likely to be about the visuals used, and that is something — country lawyer schtick notwithstanding — that can only hurt the less technological party.

That finding is also quite consistent with hundreds of post-trial interviews that we have conducted. It is quite rare these days to come across a former juror criticizing technology for being too fancy or too expensive. When technology fails, the more common accounts are that: a) the attorney didn’t know how to use it, and wasted our time, or b) it was repetitive, and wasted our time, or c) we couldn’t understand it, so it wasted our time (see the theme?). In the more common instances where technology doesn’t fail, jurors just see it as one of the many tools that were used to help them understand the case and to make a good decision.

Recommendations for ‘Looking Good’ When Compared to the Other Party

1. Don’t be the party making less use of technology. Doing that doesn’t make you seem simple and honest, and doesn’t make the other party look like deep pockets. It only sacrifices the advantage of better teaching (see Part 2 of this series), while also risking the message you are less prepared,and less interested in clearly explaining the case to the jury.

2. Do use a continuous visual approach when you can. In opening statement, closing argument, and even witness testimony, relying on a visual strategy that is fully integrated with your verbal strategy is more effective. Jurors pay better attention and perceive a more prepared advocate when you have both words and imagery for each important point.

3. Use a professional. Your job is to focus on the evidence, the law, and the persuasion. Someone else’s job should be to make sure the technology works. Technology is good, but an attorney fussing with technology is an irritation. Hire someone to sit at counsel table and call-up, zoom, and highlight documents. That person should have redundant systems (more than one hard drive with the exhibits) and should test everything in advance. You also need a person with the the skills to conceptualize and execute demonstrative exhibits before and during trial.

4. Consider cost-sharing. For many cases, each party will have their own trial technician and their own set of equipment and exhibits. The reasons for doing that (you’re used to working with your own person, you don’t completely trust the other side) are good reasons, but the redundancy that is built in to it is part of what makes litigation so expensive. If the two parties share the expense, however, and use a professional trial technologist, our experience is that you can trust that they will be efficient, neutral, and fair.

______

Other Posts in This Series:

______

Image Credit: Eyechartmaker.com