By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

In my line of work, I find myself on my feet giving presentations quite often: marketing talks, CLE seminars, strategy sessions. I prepare for those opportunities pretty extensively, but here is one thing I don’t do as part of that preparation: I don’t sit and review my notes. I do prepare notes, and I do make sure that I devote plenty of time to planning out what I’m going to say, for example, when a given slide is on the screen. That’s especially true since I don’t believe in text-heavy slides that, in effect, put the speaker’s notes up on the screen. So, the content is always planned out. But once I’m done writing those notes, I don’t passively read them. Instead, if I have time, I’ll practice the presentation on my feet — using notes when I need to, but purposefully weening myself off those notes.

And, if I don’t have time to practice on my feet, I’ll do the next best thing. I’ll record my presentation using a digital recorder, or these days, my phone, and then I will listen to my own presentation several times as I’m doing other things, like shaving or driving to work. It is my belief that this form of review and practice is much better than silent study. It gets me more quickly to the point of being familiar with the content so I can deliver it extemporaneously, and it builds confidence. That has been my experience, and now there is research to back it up. Two memory researchers from Canada (Forrin & MacLeod, 2017) conducted an experiment showing that there is a memory advantage when saying words aloud, as opposed to hearing them or reading them. And the next best thing to actually saying them out loud is to hear them, not just in anyone’s voice, but in our own. In this post, I’ll briefly look at why that is the case, and share some rehearsal tips.

The Reason: Production and Self-Reference

The memory advantage we have when actually speaking out loud is called “the production effect,” in the sense that producing rather than simply reviewing content is more active, more engaging, and more likely to stick. Based on research reviewed in the article, the effect is well demonstrated, showing that saying words aloud, or even mouthing, writing or typing them, leads to better recall than passively reading them.

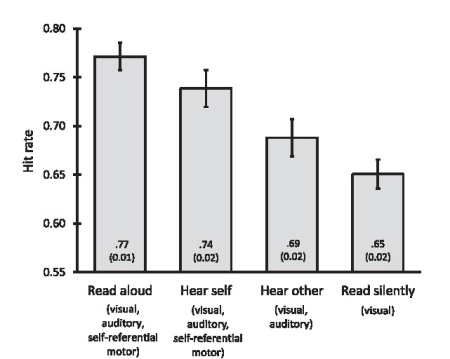

The recent Canadian study, however, was the first to focus on that next-best alternative of hearing your own voice. They compared four preparation conditions: reading words aloud, hearing oneself speak aloud, hearing another speak aloud, and reading silently. Testing the recall two weeks later, they found that the different methods of review were more to less effective in that order.

The “read aloud” version is best because you’re active in producing it in that moment. But the condition of hearing yourself is second best, due to a self-reference effect. The authors explain, “Recollecting that it was you who said a word benefit[s] memory above and beyond recollecting that you heard it or read it.” It is a more memorable and convincing way to prepare because it is you.

The authors summarize: “Put simply, the present results suggest that production is memorable in part because it includes a distinctive self-referential component. This may well underlie why rehearsal is so valuable in learning and remembering: We do it ourselves, and we do it in our own voice. When it comes time to recover the information, we can use this distinctive component to help us to remember.”

The research in this case just used a list of 160 nouns. It would be interesting to see the theory tested in more realistic speech preparation conditions, but there’s good reason to believe that the effect could be even stronger. When you do a stand-up speech (an opening, closing, oral argument, or CLE), the fact of hearing yourself wouldn’t just carry a memory advantage, it would also promote confidence. Hearing yourself do it is a form of self-persuasion, and that translates into greater credibility.

The Best Practices: Talk or Listen

The implication here is that, when it is important that you come across as clear, prepared, and confident, the gold standard is to practice on your feet. Any time that you spend reading over your notes, or constantly revising notes, is going to be time less well-spent than time on your feet in practice.

You don’t want to recite your speech, either from the page or from memory, but you also don’t want to improvise off-the-cuff. The happy mid-point is to speak extemporaneously, knowing the structure and the content very well, but choosing the exact words in the moment. The best means of preparing yourself for that is to practice doing it on your feet. So find some staff or colleagues as a test audience, or even find an empty room and just speak.

And when you cannot do that, or to get ready for doing that, find a recorder. Record yourself giving the presentation once, and then listen to it several times (my magic number is 10). I have found that this can be a pretty good substitute, and an excellent supplement, to live rehearsal. Hearing the content and hearing it delivered in your own voice just seems to help in pumping it into your brain.

I understand litigators are busy and, particularly in the crush of trial, practice can and often does take a backseat. But that is exactly why busy litigators should not waste time with a less effective preparation method like reading one’s notes. Get to a good version, and then start rehearsing it, improving it as you go.

______

Other Posts on Effective Public Speaking:

- Don’t, uh, Necessarily Worry About “Um”

- Go Ahead and Talk with Your Hands, But Know What You’re Saying

- Drop Pitch for Greater Power

______

Forrin, N. D., & MacLeod, C. M. (2017). This time it’s personal: the memory benefit of hearing oneself. Memory, 1-6.

Image credit: 123rf.com, used under license, edited