By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

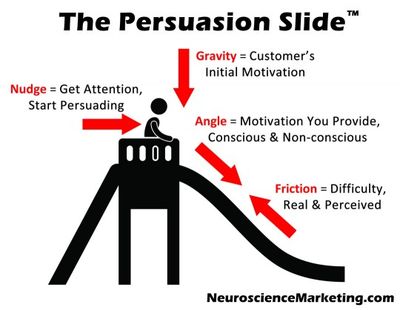

Some great practical ideas for persuasion come from the field of marketing. To be sure, not all apply in legal settings, but marketing offers a laboratory where the practical aspects of human influence can be addressed in a situation that often carries high stakes and measurable results. I recently came across one marketing idea from Roger Dooley’s Neuromarketing blog that provides a perfect way of explaining and differentiating the various forces at work in any persuasive situation. The idea is called “The Persuasion Slide,” and it starts with the simple physics involved in an ordinary playground slide. Like a good trial metaphor or demonstrative exhibit, the illustration provides a simple and immediately meaningful way to understand a more complex process.

It is possible that practical persuaders’ eyes might start to glaze over when they hear about “models” of persuasion. But this particular idea carries more than just theoretical benefit. It provides a practical way to identify and discuss the very real components of persuasion, and to be reminded of some influences that could otherwise be overlooked. In this post, I’ll share Mr. Dooley’s model and layer on my own ideas of what it suggests in a legal persuasion context.

Without further ado, here is the model:

(Copyright and trademark, Roger Dooley, Neuromarketing — used with permission)

The idea is that the process starts with some outside push toward attention (a nudge) and then uses a target’s internal motivation (gravity) along with additional motivation provided by the persuader (angle), in order to overcome resistance (friction) and get to the goal. While Roger Dooley uses the word “customer,” he could have just as easily referred to the “audience” or the “persuasive target,” since these factors are at work in any situation of attempted influence through communication. The model is also very simple — just like every good hueristic. Applied to courtroom persuasion, however, it carries some important implications and reminders.

Nudge

At the top of the slide, something pushes you off. In marketing, that nudge is anything that breaks through the clutter and makes the customer willing to consider a call to action (e.g., “24 Hour Sale!”). In court, persuaders should be looking for a comparable nudge. Don’t presume that the jury, the judge, or the arbitrator is paying full attention simply because their role calls for that. In complex cases, in fact, they need to be doing more than simply paying attention, they need to be working to follow the case. What nudges the fact finders toward that kind of attention? In public speaking we call it the “attention step,” or the “payoff,” and in popular music we call it the “hook.” In opening statement, we call it the “silver bullet” that grabs your decision maker in the first few minutes and distills the case to its essence in a memorable way. But beyond the introduction, maintaining attention is a continuous battle because the brains of your listeners are continuously selecting and shedding detail. So persuaders need to communicate as though they’re constantly pouring sand into a colander. With clear expression, good visuals, and impactful language, your message in trial should highlight the most important takeaways, in effect saying, “Listen to this,” and “Remember this.” It isn’t a one-time nudge, but a constant nudge.

Gravity

Of course, you’re going nowhere on that slide if there isn’t some force pulling you down. In persuasion, that force starts with the motivation the audience brings themselves. As Roger Dooley notes, persuaders need to be aligned with their target’s motivation, not their own. As I’ve emphasized before, jurors and judges are like other persuasive targets in engaging in motivated reasoning, meaning that they will adapt a leaning, often based on implicit factors that aren’t fully conscious, and then come up with reasons to support that leaning. That is in contrast to a rational legal model that expects people to start with evidence and work their way to the conclusions, but it is consistent with a great deal of psychology showing that the conclusions often come first. The attitudes that a decision maker has to begin with supply a kind of gravity for the message. Of course, your case might be like the Wright brothers and defy that gravity, but wherever there is a way to do so, it is far better to find a way for those preexisting motivations to work for you. Sometimes that can mean identifying actual attitudes though a juror questionnaire or oral voir dire (e.g., “corporations are greedy”) and finding ways to adapt your case to those attitudes (e.g., “the profit motive led the company to do the right thing in this case”), and at other times it can mean finding more universal motivators, like the values of fairness, security, or care, and adapting your case to highlight those values. In all cases, though, it helps to ask “before and apart from your message, what forces are pulling on the target audience?”

Angle

Your slide has to be steep enough to work and to overcome friction. The angle is Roger Dooley’s metaphor for the motivators the persuader brings to the job. In legal persuasion, this means not just the evidence, but everything the trial attorney does to put the case in the best possible light: The frame; the analogies; the story; the chapters; the visuals, the balanced use of ethos, pathos, and logos; and all of the other elements that go into what Aristotle called “artistic proof.” Those techniques cannot normally create a motivation that isn’t otherwise there, but they can help guide and direct existing motivations in particular directions — much like a slide’s angle working with gravity to move in a particular direction. Dooley points out that this angle includes not only a persuader’s conscious motivators (our intentional techniques and strategies) but the unconscious ones as well. For example, a plaintiff who spends too much time preempting what the defense will say might be unconsciously putting an angle on the case that says, “we’re very concerned about the negatives in our case.” Considering the angle in legal persuasion means looking at all the factors that influence the fact finders one way or the other.

Friction

Persuasion never takes place in a friction-free environment. Even when your slide is smooth plastic or polished stainless steel, there is some force slowing you down. In Dooley’s metaphor, that friction relates to the real or imagined difficulty the persuader faces in making a particular case to a particular audience. In legal persuasion, resistance to persuasion looms quite large: A distrust of attorneys, witnesses, plaintiffs, defendants, and others makes it safe to assume that your audience is taking nearly everything with a grain of salt. Faced with specific obstacles like skepticism, difficult comprehension, or bias, litigators might think that rationally, the fact finders should be able to get past it. And, indeed, they might, but friction is still friction and the more of it there is, the more trouble the advocate will have. The idea of friction provides a reminder to think not only about the theme that would bind jurors to your case, but also the anti-theme that would turn them off from it. It reminds us to focus not only “alpha” strategies, but on “omega” strategies as well: buttressing not just the reasons your position is preferred, but also on the reasons your position may be avoided. More basic sources of friction might also be found in a simple lack of comprehension, or in a bias that cuts against your client.

Taken together, the elements of the “Persuasion Slide” should serve as a good reminder to attorneys: It is not just a matter of giving reasons so the fact finders are convinced. There is more to it than that.

______

Other Posts on Models of Persuasion:

- Persuade Through Dialogue

- Persuade With Participation, Part One: Learn from Early Rhetoric

- Persuade With Participation, Part Two: Learn from Modern Cognitive Science

______

Photo Credit: Jonolist, Flickr Creative Commons (edited)