By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

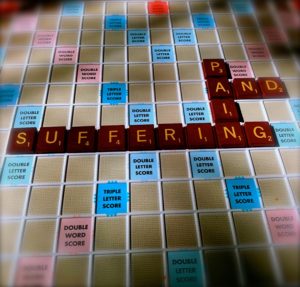

Juror 1: “The next category is ‘pain and suffering.’ How are we supposed to get to get that number?”

Juror 2: “It is just whatever we want…there’s no guidance for it.“

Juror 1: “How are we supposed to do that? Put a dollar value on pain and suffering?“

Seeing an exchange like that is pretty common when watching a personal injury mock trial. They’ll have less information in the research exercise than they will in the real trial, but ultimately, on the pain and suffering question, the won’t have much more guidance in the courtroom.

There’s a tendency to treat jury decisions on the dollar value of non-economic categories like pain and suffering as mysterious, and potentially random. But if you continue watching that mock trial, you will eventually see the process they use. It isn’t fully predictable, and it isn’t always what the law would expect, but there is a system to it. New research adds some support to that. Academics at Cornell University (Reed, Hans & Reyna, 2019, full text here), conducted three studies in which 763 mock jurors explain their own reasoning for pain and suffering awards in two personal injury/negligence scenarios. Looking at the reasons correlated with the actual awards, they found that only three factors predict damage awards: How much the injury interferes with life, any anchor number the juror has heard, and the side the juror favors. In this post, I will take a look at the research and its implications for arguing for and against pain and suffering awards.

What Predicts Pain and Suffering Awards?

Based on the research, three factors correlate with the numbers awarded for pain and suffering:

Interference

When mock jurors were asked their reasons for their pain and suffering awards, the two most frequently mentioned categories of reasoning were the extent of pain and suffering (mentioned 44.3 percent of the time), and the degree of interference with life (mentioned 46.7 percent of the time). Interestingly, that first category — the obvious one — was not associated with actual numbers awarded. But the second category was. The more jurors mentioned the injury’s interference with life, the more they awarded.

Anchoring

It has long been known that giving numbers that the jurors can “anchor” around tends to work. This study adds support to that, as providing an anchor led to significantly higher awards, particularly when it was a meaningful anchor (in this case, median income). As one mock juror noted, “I was told average annual income is $50,000 and I thought her emotional suffering was pretty tremendous so I awarded her 20 percent of this number.”

Fusion

Liability and damages are supposed to be separate stages, and research participants in this study were told to assume that the defendant had been already found liable, and that their task was solely to determine damages. Despite that, jurors in this study and others will routinely “fuse” the liability and damages questions. Those who leaned toward the defense or who questioned liability (for example, emphasizing in their comments that the defendant didn’t act intentionally or with malice), gave lower damages awards. The researchers explain, “Jurors went with their gist interpretation and not the law; apparently resulting in some discounting of the award,” calling this tendency to reduce damages based on uncertain liability “a mild form of civil jury nullification.”

What’s the Effect of Uncertainty?

One additional finding is that a focus on the uncertainty of pain and suffering calculations tends to reduce damages. In other words, “Incalculable” means “Noncompensable,” and jurors who said it is difficult or impossible to arrive at a number tended to arrive at a lower number. Participants would justify their lower awards with statements like, “Emotional pain sucks but you can’t put a price on it” or “Money will not erase ‘pain and suffering.‘”

For attorneys on either side dealing with the issue of pain and suffering amounts, the implication is to not treat the category as a black box or a random dart thrown at a target. Think about the factors that mediate the amount. Address the injury’s interference with life, use anchoring numbers if you can, and remember that your overall favorability and jurors’ leanings will also help to determine that number. The researchers conclude with the following advice:

“Thus, successful attorneys should see part of their task as helping jurors understand the gist of the injury. For a plaintiff’s attorney, this might mean developing a picture of a sympathetic plaintiff, explaining how much the injury has interfered with the plaintiff’s life, and offering meaningful anchors. A defense attorney might be more successful making the defendant appear sympathetic by highlighting the defendant’s lack of responsibility even in cases like these in which only monetary damages are at issue.”

______

Other Posts on Damages:

- Normalize Your Damages: Five Ways

- Damages: Know Your Anchor

- Remember, With Damages It’s the Message and Not Just the Math

- Consider How Jurors Arrive at Damages Numbers: In Stages and With Difficulty

Reed, K., Hans, V. P., & Reyna, V. F. (2018). Accounting for Awards: An Examination of Juror Reasoning behind Pain and Suffering Damage Award Decisions. Denv. L. Rev., 96, 841.