By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

It is well known that some people have it in for corporations, especially when these large companies find themselves on the defense side in a courtroom. Our own research has shown that a negative attitude is very common, with close to eight in ten individuals believing that large corporations tend to be dishonest and should bear a greater share of responsibility than individuals. We have been researching these attitudes for close to two decades at this point, but a new academic study (Hunter 2018) shines a light on two additional questions: How much of an effect does anti-corporate bias have on damage amounts, and does it matter whether the company is a familiar name or not?

In her doctoral dissertation, Kirsten Deming Hunter addresses these questions using an online study with 226 participants. The study is based on a real-world products liability case involving the seatbelts in a Honda vehicle. She also uses the Persuasion Strategies Anti-Corporate Bias Scale. After revalidating the instrument based on our original raw data, she notes that the measure is “well-tested with regard to identifying meaningful differences between jurors with attitudes that pose high-financial risk to corporate defendants versus those who do not,” and that “the ACBS showed consistent ability to predict when anti-corporate bias posed litigation risk to corporate clients.” So, in this post, let’s take a look at what our scale has been doing out in the world. I will identify four important takeaways from the research study for corporate defendants, or anyone else wanting to understand more about the form and extent of the bias.

Anti-Corporate Bias Does Impact Damages

The researcher looked at total awards given by mock jurors, and found that the measured levels of anti-corporate bias played a role in determining those awards: “Anti-corporate bias as measured in this study predicted higher compensatory awards in all analyses.” This is consistent with other research, including our own, indicating that anti-corporate bias drives negative sentiments toward companies and increases the desire to punish corporate defendants.

But Not to an Extreme Degree

The effect on damages was statistically significant, but still relatively modest. The researcher expected it to have a higher effect, but it ended up explaining a proportion of the variance that in different scenarios still ended up being in the single-digits. In some ways, this goes to show there is still much about the process of translating injuries into dollars that are not well understood. It also provides the healthy reminder that jurors are responding to the full case and not just bringing in and applying their biases. The finding of a minor effect for anti-corporate bias might also be taken with a bit of caution. In addition to being online research (where participants don’t have as much exposure to the corporation as jurors will), it also used a fact pattern in which liability was admitted. When a company denies fault and is then subsequently found to be at fault, pre-existing bias against that company could play a greater role. In civil litigation, even a small difference can mean a lot of money, so anti-corporate bias is still worth tracking as part of the overall profile applied to jury selection.

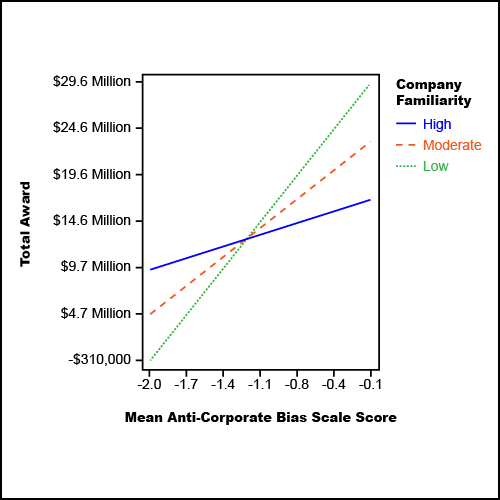

But Especially If the Company is Unfamiliar

The most interesting result of the study has to do with the role of mock jurors’ familiarity or unfamiliarity with a company. Because familiarity is correlated with liking, and leads to stronger attention and more confident decision making, one might think that familiarity would play an important role in influencing damages. However, familiarity by itself was not an important predictor of award amounts. But familiarity played an important role in moderating the effects of anti-corporate bias. In general, greater bias means higher awards. However, when the company is highly familiar, the slope of that difference is much more modest.

The author explains, “Company familiarity moderated the relationship between anti-corporate bias and awards; the total amount of compensatory damages awarded by prospective jurors with high levels of anti-corporate bias was significantly less when they were also highly familiar with Honda Motor Company.” That suggests that, when a company is familiar, it is probably more important to assess attitudes toward the actual company rather than general anti-corporate bias. It is also a reminder that people are assessing the credibility of the company itself, and underscores the fact that humanizing the company can help.

The author explains, “Company familiarity moderated the relationship between anti-corporate bias and awards; the total amount of compensatory damages awarded by prospective jurors with high levels of anti-corporate bias was significantly less when they were also highly familiar with Honda Motor Company.” That suggests that, when a company is familiar, it is probably more important to assess attitudes toward the actual company rather than general anti-corporate bias. It is also a reminder that people are assessing the credibility of the company itself, and underscores the fact that humanizing the company can help.

And It’s Best Measured as an Average

A final reminder from the research is that anti-corporate bias is best measured as a continuous variable, in this case, an average of a seven-item scale. Measured that way, as in the chart above, anti-corporate bias has a clear effect. It is less clear when it is more simply conceived as a dichotomous variable. When we are just looking at “high” or “low” anti-corporate bias, the attitude loses much of its predictive power. According to the author, the scale predicts damage amounts approximately twice as effectively when left as a continuous variable, and not converted into a “high” or “low” dichotomy. In practical use, this is a reason to include many questions relating to anti-corporate bias. When you have the opportunity to receive and analyze a questionnaire before the actual voir dire, the best practice is to use all seven questions and calculate juror scores as an average.

______

Other Posts on Anti-Corporate Bias:

- Expect Anti-Corporate Attitudes to Persist and Grow

- Bad Company: Investigate the Sources of Anti-Corporate Attitudes

______

Hunter, K. D. (2018). Company Familiarity Moderates Anti-corporate Bias and Jurors’ Compensatory Award Amounts(Doctoral dissertation, Fielding Graduate University).