By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

When you’re a campaign front-runner, you can expect a little extra attention, and Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson is now finding that out. The controversy is based on claims that he received and turned down a scholarship offer from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Following some journalistic digging and subsequent clarification by the Carson campaign, it appears that Carson didn’t apply or receive any kind of formal offer from the academy. In his defense, the candidate has emphasized that he is remembering events from fifty years ago, and the lines could easily have blurred as Carson remembered the advice he received from a friendly general as an offer of admission and scholarship. A similar reconstruction error could be found in the recent downfall of NBC anchor Brian Williams who frequently told the story of being in a helicopter that was shot down over Iraq in 2003, but who actually rode in a helicopter that was forced to land when it’s companion helicopter had sustained fire. It is possible, some suggested, that through subsequent tellings, the details just tended to blur in Williams’ mind.

Of course, many don’t buy that it is a reconstruction error when it comes to either Williams or Carson. But the two stories do remind us of a generic weakness in human memory that matters in a legal context. The law generally assumes that memory provides clear access to an event as long as the witness is a competent and reliable narrator and is under oath. But that fails to appreciate the profound extent to which memory is reconstructed. As a result, it fails to account for the possibility that the honest and unbiased witness can be dead wrong. Instead of acting as a simple storage and retrieval system, memory is a complex process involving active transformation at every stage. In this post, I’ll share some of what we know about the reconstructive process of memory as well as a few implications for dealing with memory in testimony.

What We Know About Memory

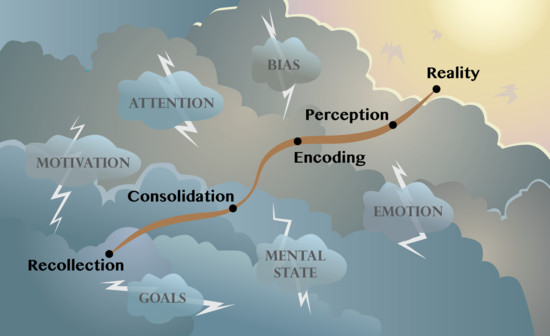

For most of us, the brain isn’t a camera or a tape recorder. It doesn’t simply capture fresh experiences before those experiences decay over time. Instead, the processes of memory are extraordinarily complex. According to a helpful write-up by BrainBlogger’s Sara Adaes, “We tend to place too much trust in our memory and firmly believe that everything happened exactly as we recall it.” When we think back on a prior event, we aren’t just retrieving a memory the way you might retrieve your keys from your house. Instead, the retrieval is structured at every phase of the process. At the moment it happens, our ability to perceive it isn’t perfect or neutral. Instead, it is influenced by a variety of filters we have in place. The resulting individual perception then has to be encoded, or reduced to a simplified and distorted version that can be stored. Over time, that memory is consolidated, or “chunked” with other memories into organized systems of knowledge and belief. With the addition of new memories, that old memory can be changed, enhanced, or discarded. But each and every time the memory is accessed, we are creating a new memory — not of the actual event, but of our recollection of it. When we say “remember,” what is being remembered might be, not the direct perception, but the encoding or the prior retrievals.

Here is a handy chart to represent that process.

Seeing memory as a complex storm of phenomena has some advantages, particularly to those who work in a field like law that uses memory as one of its primary tools. Memory isn’t reality, and there isn’t a straight-line relationship between the two. Instead, there are a series of steps that are beset on all sides by psychological factors tending to warp and bend the memories in different directions. Bearing in mind that memory is constructed reminds us that certainty is not the same as accuracy, retrieval tends to alter the original memory, and that the whole process is inherently selective like a flashlight in a darkened room.

How Should We Adapt to Memory in Court?

There are a ton of implications, probably too many to remember. But helpfully, I’ve written on some here before, particularly as they relate to crossing and defending witnesses who might have shaky memories. Looking at the bigger picture, though, here are a few additional thoughts.

Remember that We’re Only Dealing With Reconstructions

There is no escaping the fact that a witness’s memory will be a reconstructed version of events. It can still be a better or worse reconstruction, and closer or further from the truth. But it is never unfiltered reality. We are used to dealing with that reality in eyewitness cases (though still typically according that testimony more credibility than it merits). But it is worth remembering that reconstruction affects all testimony based on memory, which pretty much means all fact testimony.

Be Mindful in Your Reconstructions

When remembering an oft-told story, we aren’t so much remembering the initial event as we are remembering earlier tellings of the story. Witness preparation can end up being a big part of that retelling. Anything that is repeated is more likely to be retained, but we have to remember that the repetition is adding to the memories, and practicing bad answers is worse than no practice at all. In preparation sessions, it makes sense to talk through the substance of the answers to key questions before going into practice mode.

And Remember that Alternatives to Memory Are Often Just as Good or Better

I often work with doctors prior to testimony, and many of them feel bad for not remembering a particular patient or a particular event. Even when it is in context of hundreds or thousands of patients or events, the doctor feels at a disadvantage if they don’t have that independent recollection. What they don’t realize is that the alternatives to that recollection — records and their pattern and practice — can often be better than memory. When doctors testify about their pattern and practice, for example, they’re sharing what they do in every case, and that can be much more credible and influential than a hazy reconstructed recollection of a particular patient.

All in all, our brains are capable of some amazing feats, and the limitations of memory are more of a feature than a bug, making it possible for us to deal with reality as it happens, and learn from experience without being overwhelmed by detail.

______

Other Posts on Memory:

- Don’t Confuse Certainty with Accuracy when It Comes to Witness Testimony

- Chunk Your Trial Message

- Remember that Memory is Selection, not Retrieval

______

Image Credit: 123rf.com, used under license