By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

Language is the cognitive and social invention that made it possible for us to resolve conflicts with reason rather than force. Language begat law, and law in turn begat litigation. Lawyers work with words, and particularly those who are in the trial business understand very well that language isn’t neutral. Instead, it puts its thumb on the scale by conveying effects beyond literal meaning. One dimension of the power of words lies in valence — the association of a given word as positive or negative. Years ago, theorists (Boucher & Osgood, 1969) offered up the aptly-named “Pollyanna Hypothesis” that communication tends toward the positive, and that it is not simply a human choice to “look on the bright side” but a bias embedded in our language system. Now, this year, a truly massive study of languages around the world seems to offer very compelling support for the hypothesis of a “universal positivity bias.”

Covered in a recent post in Psyblog, the new study was conducted on a monumental scale, focusing on billions of words used in various contexts within multiple languages. It looked at words at varying levels of common use, and how people reacted to those words as positive or negative. The result offers broad confirmation of the “Pollyanna Hypothesis:” In use, language does indeed show a strong bias toward the positive. That finding provides an important reminder to litigators: Mind your valence. While many aspects of advocacy might push you toward the negative (what is false, what is unfair, what is harmful), there is a strong natural advantage in orienting your case toward the positive (What is true, what is fair, what is beneficial). In this post, I’ll take a look at this new language study and share three different ways this emphasis on the positive should be used by trial lawyers.

The Research: Communication Leans Toward the Positive

What stands out about the study (Dodds et al., 2015) is its comprehensive focus. A total of 14 named authors, along with assistants, looked at 24 distinct contexts for source language (including Twitter feeds, newspapers, movie subtitles, music lyrics, and novels), and evaluated a staggering number of words: 100 billion from Twitter alone. The text was drawn from 10 languages, including English, Chinese, Spanish, French, German and Russian. Native speakers of each of these languages rated the unique words on a scale from negative to positive based on their own individual associations. But to guard against ideosyncratic reactions, the research team obtained 50 individual ratings for each word, for a total of approximately 5 million individual ratings.

In all of the samples evaluated, the valence of language used averaged well above the neutral point, and the team observed this tendency toward the positive in both the frequently-used as well as the rarely-used words. As the lead author, Professor Peter Dodds, summarized, “We looked at ten languages, and in every source we looked at, people use more positive words than negative ones.” Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study is available for free in full text.

The Implications for Your Positive Message

For trial lawyers, it isn’t just a matter of picking from a list of ‘happy’ words. Instead, it is a matter of considering the positive in the way you describe your case and frame your arguments. Let me share three examples of what I mean.

Frame It as a Positive

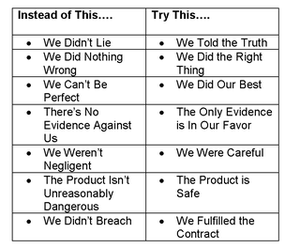

The same thought can often be expressed in a positive or negative manner. I have used this table before, but it is worth repeating in context of these results.

It is a subtle difference, but it works. The language on the positive side frames the argument in your terms, while the language on the negative side frames it in their’s.

Cover the Good Before the Bad

It is rarely a good idea to come out swinging, attacking the other side right out of the gates. Instead, it is generally more strategic to build the “What we did well” case first, because that is the foundation that will give you the credibility to launch those attacks with greater force later on. This advice to build your own house before you start throwing rocks at the other side matters for both plaintiffs and defendants. The products liability plaintiff, for example, will want to build a case for the client’s own good choices and reasonable care prior to attacking the manufacture or design of the product. And the medical negligence defendant will similarly want to create a strong defense for their own care as a first step in refuting the actual claims.

Promote the Ultimate Good of Your Preferred Verdict

What good is done by your preferred verdict? Lawyers aren’t used to that question because the verdict is framed as a claim about what is true, not about what is good. But jurors are motivated by factors that range far beyond the desire to just fulfill their oaths and deliver an answer to the court. Just as language tends toward the positive, jurors do as well. They want to feel like they are helping to promote a positive outcome. A prosecutor in a criminal case, for example, shouldn’t treat conviction as “regrettable, but necessary,” but as something that is a positive result: balance, justice, protection. The civil plaintiff should be able to talk about the good that will be done by a sizable verdict, to the extent they’re allowed to. The civil defendant should also talk about the advantage in a jury verdict that upholds a principle, like personal responsibility for example.

Language is our only medium for thought, and that fact can make it hard to think about language: It is the water we swim in and can’t ever actually leave. But litigators know implicitly that language is power. And, based on the research, we have reason to believe that this power tends toward the positive.

______

Other Posts on Language:

- Check Your Language Level

- Make Your Trial Theme Cinematic…Or At Least Memorable

- Use Metaphors to Touch Your Fact Finders

______

Dodds, P. S., Clark, E. M., Desu, S., Frank, M. R., Reagan, A. J., Williams, J. R., … & Danforth, C. M. (2014). Human language reveals a universal positivity bias. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112: 8, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1411678112

Image Credit: 123rf.com, used under license