By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

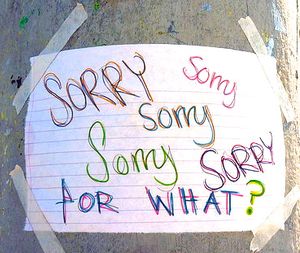

When someone causes you some kind of harm, say they step on your foot, they’ll say “I’m sorry.” When you’ve experienced some kind of misfortune or loss, like a death in the family, people will again say, “I’m sorry.” In that latter example, they aren’t (we presume) admitting that they had anything to do with the death. In the first example, “sorry” means “I wish I hadn’t done that.” In the second example, “sorry” means “I recognize your loss.” Two different acts that just happen to share the same word, “sorry.” As we’ve noted before, letting jurors, judges, and opposing parties hear an apology can be effective when you are responsible, or are likely to be found responsible, for at least part of the damage at issue in the case. But what about when you’re not? Does that second kind of “sorry,” meaning “I recognize your loss, but without accepting responsibility for it” create a persuasive advantage as well?

According to some new research, yes, it does. Calling them “superfluous apologies,” three researchers from Harvard Business School and the Wharton School (Brooks, Dai, Schweitzer, 2013) just published an article describing their study on the effectiveness of that act of apologizing without accepting blame. Their experiments demonstrated that the nonresponsibility-based, or “superfluous” apology, does indeed work: It builds trust and improves persuasive effectiveness. This post takes a look at the study and discusses a few implications for litigation.

The Study: I’m Sorry About the Rain

In a research report on four studies published in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science, the researchers looked at “expressions of regret for an undesirable circumstance that is clearly outside of one’s control.” One study used a confederate who was kept in the dark about the purpose of the study. The individual randomly selected people to approach on a rainy day. Half the time, he approached the person and said: “I’m so sorry about the rain! Can I borrow your cell phone?” For the other half, he skipped the apology and went directly to the request, “Can I borrow your cell phone?” Which approach worked better? Forty seven percent of those who received a superfluous apology were willing to hand over the cell phone, compared to only nine percent of those who did not. That effect could be due to the simple existence of more communication in the first condition, not necessarily the apology. To guard against that, researchers used other studies to also test the superfluous apology condition against a neutral communication condition (e.g., “how are you?”) and still found an advantage in the apology. Overall, it appears likely that the statement about the rain is helping to forge a better kind of connection. “By issuing a superfluous apology,” the researchers believe, “the apologizer communicates that he has taken the victim’s perspective, acknowledges adversity, and expresses regret.” They go on to conclude, “Superfluous apologies represent a powerful and easy-to-use tool for social influence. Even in the absence of culpability, individuals can increase trust and liking by saying ‘I’m sorry’-even if they are merely ‘sorry’ about the rain.”

Two Litigator’s Rules for ‘Superfluous Apologies’

Taking another’s perspective and acknowledging adversity and regret can be important features of a litigation message as well. So, what should trial attorneys do with the finding that it is useful to acknowledge a loss, even if one had nothing to do with it? I’d say, there are two conclusions.

One, Acknowledge Death, Pain, Loss, and Even Inconvenience

As I’ve written before, legal cases are about loss. Sometimes it is a large loss (like a life), and at other times it is a relatively smaller loss (like money or opportunity). In all cases, showing that you understand this loss is a form of identification. The acknowledgement builds a bridge by communicating a number of things: I am human, I see what you see, and I am similar to you in thinking that it is unfortunate. When making that acknowledgement from the defense side of the courtroom, the critical factors of that acknowledgement are that it is sincere (it doesn’t sound pro forma), it is complete (it doesn’t leave out anything jurors would see as a loss) and it isn’t weakened too much by argument (it isn’t immediately set aside by a “but…”).

Two, Don’t Let Acknowledgement Get Confused With Responsibility

As effective as it is to acknowledge and identify with another party’s loss, there is still a great risk in being seen as offering a confession for that loss. Because the word “sorry” has these two meanings (“I’m sorry I did it,” versus “I’m sorry you experienced that”), you should avoid using the word “sorry” unless you expressly mean to take responsibility for something. If you don’t, then it is better to express “sorrow” or simply “understanding” of the situation the other party is facing. Take some care in how you offer that acknowledgement, because if jurors see it as a “fake” apology, that can be worse than making no apology at all. Here are a few ways to say it:

Like any physician, what Dr. Smith wants is a good outcome. That is what the training, the testing, and the precautions are all aimed at: a good outcome. As an experienced doctor, he knows that happens most of the time, but not all of the time. When it doesn’t happen, it is only natural to feel regret, and that includes a great deal of sorrow and sympathy for the patient and the family.

This company is in the business of making safe products. So, those who devote their ideas, research, and testing are naturally dismayed to find out when something as tragic as this has happened. Even when the product didn’t cause or couldn’t have prevented the injury, there is still the recognition that something tragic occurred.

Smithco, like the defendant company in this case, had high hopes for this business deal. It represented a common goal, a joint enterprise, and an exciting challenge. So there was an emotional commitment on both sides. When the deal failed, Smithco regretted that deeply: It was a lost opportunity, and it is always sad to see that.

The common thread in these three examples is that they acknowledge a loss, but without giving a formal “I’m sorry” and without necessarily accepting blame for the outcome. It isn’t as clear as saying, “I’m sorry about the rain,” as tested in the study, but it is likely to bring about a similar increase in credibility and a greater opportunity for influence.

______

Other Posts on Apologies:

- The Key to the Defendant Apology: Say What You Mean, and Mean What You Say

- Apologize: The Right Way at the Right Time

- Say Your Sorries and Settle Already

______

Brooks, A. W., Dai, H., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2013). I’m Sorry About the Rain! Superfluous Apologies Demonstrate Empathic Concern and Increase Trust.Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1948550613506122.

Photo Credit: dreamsjung, Flickr Creative Commons

Commons