By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

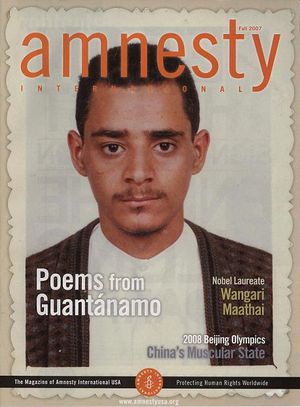

The reason probably, at least partially, has something to do with justice. The cases that should remind us the most of that can sometimes feel like lost causes, like the tragedy of Adnan Latif. This young man traveled in 2001 from his native Yemen to Pakistan, near the Afghanistan border, where he was captured in a post-9/11 military sweep and ended up at Guantanamo Bay. According to his lawyer, David Remes, Mr. Latif was seeking medical care following a severe head injury sustained in a car accident. While the government maintains that he trained and fought with the Taliban, there is no information in the public record to back that up, or to support that he had caused harm to anyone in his life. What became clear over the years to most of those closest to his case was that he didn’t belong in Guantanamo. Administrative review boards recommended that he be repatriated back to Yemen in 2004, again in 2006, and again in 2008. Yet he continues to be in U.S. detention when President Obama’s Guantanamo Review Task Force clears him for transfer in 2009. Then in 2010, he is still in Guantanamo when a District Court judge declares his detention unlawful in a 30-page ruling. That decision is then overturned by a divided D.C. Circuit Court (based on a presumption of deference to the government’s claims), and ultimately the case is denied certiorari by the Supreme Court last year without comment.

Having never been charged with conducting or planning any crime or terrorist act, having been locked in Guantanamo for a decade, having spent a majority of that time in solitary confinement in a dramatically deteriorating psychological and physical state, and having been apparently ‘freed’ from U.S. custody no fewer than five times without effect, Adman Latif finally found release last week in the only way that remained open to him: He died. The announcement was made last Tuesday on the 11th anniversary of the September 11th attacks.

Many, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, The American Civil Liberties Union, and The Center for Constitutional Rights have written with passion, eloquence, and deep frustration on the messages carried by this tragedy. While there is no need to make a saint of Mr. Latif, there is much to criticize in a failed process, including a broken promise from the President to close Guantanamo Bay and either try those that remain in federal court, or repatriate them to countries that will respect their human rights. That hasn’t happened for the 167 who are still in Guantanamo Bay, and may not happen for prisoners of the future if the administration succeeds in its continuing defense of indefinite detention at Guantanamo. There is a wound that extends beyond the island. As the New York Times wrote yesterday, “This brutal outpost has tarnished American justice every day of its existence.”

It isn’t my goal in this post to try to improve on the already well-stated arguments buttressed with the reflections of many of the lawyers working these cases. Instead, my purpose is to speak to a related set of concerns that should matter to litigators working all kinds of cases. The legal profession has long recognized that lawyers carry a special set of skills allowing them to highlight and address injustices, and for that reason, lawyers carry a special responsibility in cases like these. The dedication of Adnan Latif’s lawyers, David Remes, Marc Falkoff and others, as well as the many lawyers across the country working for other detainees, provide us with two important reminders:

Find the Cases that Matter Most

Every case matters, but in a lawyer’s career there will always be some that resonate more strongly with the feeling of having done, or at least having attempted, good. As part of the special role that lawyers hold, the profession expects at least a portion of an attorney’s services to be dedicated not in pursuit of fees or shares of verdicts, but for the benefit of the public. Of course, the legal campaign to support Adnan Latif and the many others like him has been provided on a pro bono basis, and the failures along the way are the fault of a constitutionally dubious system of laws and policies, and not the fault of the lawyers desperately trying to work within it.

And other lawyers can share that burden. There is no shortage of pro bono opportunities, yet competition in the legal marketplace, as well as tough economic times, have resulted in many law firms decreasing the time and emphasis placed on pro bono work. Finding the time for the 50 annual hours the ABA recommends, however, can be an important way of building your network, enriching your experience, and reminding you of the values that brought you and your colleagues into the profession in the first place.

While the pro bono expectations for lawyers are probably familiar to most, what may be more of a surprise is that many trial consultants also work on a pro bono basis. For me, it helps that I have been affiliated with law firms that have had a strong commitment to pro bono representation, including (full disclosure) firms that have been involved in Guantanamo detainee cases. We are frequently involved in pro bono cases, and some of my proudest experiences have been in that category. Across the country you will find many members of the American Society of Trial Consultants who have indicated a willingness to be involved in pro bono projects, or you could contact the society’s Pro Bono Committee which serves as a central access point for pro bono involvement.

The cases that matter most, of course, may not be pro bono cases, but may instead be court-appointed, or reduced-fee, or simply cases that you would otherwise not be able to take: like a contingency case with a relatively low chance of recovery. In all cases, lawyers will do well to try to do good.

Find What Matters Most in All Cases

While there is nobility in providing legal support where it could not otherwise be afforded, that isn’t the extent of nobility in the legal profession. Some cases, like Mr. Latif’s and those of other detainees, are important because they raise fundamental questions of this country’s commitment to human rights and justice. Next to that, it is easy to feel that the typical contractual or employment case is hollow in comparison.

Yet it is worth remembering that every case — every case — intersects in some way with the broad notions of justice that the law is supposed to protect. A good advocate not only selects good cases, but also finds the “good” in the case that has been selected. Whether you are volunteering your time or billing at a high rate, you are contributing your skills to a dispute where some basic equities are at stake. And more broadly, you are working within a system for resolving disputes based on reason and advocacy, and not based on simple power or force.

A skilled legal persuader will work with the case she has to locate that kernel. Even when it is a small kernel, there is still a dimension of universal morality that your case should appeal to. That isn’t just what makes your argument ethical, it is what makes it effective as well. And even when the party you represent doesn’t have natural claim to a greater share of that morality than an opposing party, there is still virtue in participating in a process that asks for the best arguments from each side, then entrusts a neutral or group of neutrals to make the final decision.

For Adnan Latif, it is easy to conclude that this process did not work. It not only failed one prisoner, but it also arguably failed this country’s commitment to law and human rights. Mr. Latif was the ninth detainee to die at Guantanamo, six of those were declared suicides, and there is reason to believe that this might be the seventh. Mr. Latif had spent much of his decade at Guantanamo not only in solitary confinement but also in physical restraints. Part of his declining condition was due to hunger strikes that resulted in him being force fed through a tube. As he wrote in a letter to his lawyer in 2010, “Ending [this life] is a mercy and happiness for this soul. I will not allow any more of this and I will end it.” And he added, “a world power failed to safeguard peace and human rights.” It is too late for justice to be served in his case, but not too late for it to be pursued in other cases. According to Zeke Johnson, Director of Amnesty International USA’s Security with Human Rights Campaign, it is an ideal time to work and to communicate on behalf of another detainee Shaker Aamer who has a comparable case calling out for either charges or release.

Other Posts on Social Justice:

______

Photo of Adnan Latif and magazine cover image used by kind permission of Amnesty International.