By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm

Imagine a typical employment discrimination case, subject to all of the ambiguities of human motivation. To the plaintiff, it is a story of good if not exceptional work performance cut short by a decision to terminate based on race, gender, age or disability. To the defendant, it is a story of enforcing job expectations broadly on all employees, including those who happen to be in protected categories. Given that a biased motive is rarely declared, it generally needs to be inferred from the circumstances. That act of inferring can invoke many of the subtleties of the fact finder’s world-view, attitudes, and bias.

But the question is, who decides? The recent history of employment litigation is a history of shifting fact finders. In the early days of Title VII, it was judges. Then after the Civil Rights Act of 1991, the door was open for employment plaintiffs to seek verdicts and damages from juries. More recently, as employers have moved to mandatory arbitration clauses, the dominant fact finder has changed yet again. Some dimension of choice remains, particularly for defendants, and that choice is important. In this post, I take a look at the question from the defendant’s point of view to share some of what we know on how judges, arbitrators, and juries compare in the context of employment cases.

Initially, you might think that we can get that answer just through a simple statistical look at who wins most often in each venue.

Isn’t It Just a Matter of Statistics?

After all, what is easier than looking at outcomes? And indeed, there have been many analyses over the years comparing results in different venues. Here are some representative comparisons.

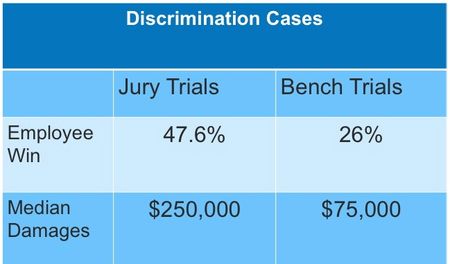

First comparing judges versus juries, the Department of Justice’s “Civil Trial Cases and Verdicts in Large Counties” provides the initial impression that judges are much better friends to employers than juries. According to this comparison, plaintiffs win nearly half the time in front of juries, but only a quarter of the time in front of judges. In addition, the jury tends to award three times the damages.

When we add arbitration to the mix, the data tend to show that arbitrators, perhaps predictably, are more like judges than juries. An analysis this year (Colvin & Pike, 2012) confirms the perception that, for the employer, arbitration is best and state courts are worst.

This is compelling data, but at the same time, it arguably leaves out the most important factor: case selection. A plaintiffs’ attorneys who have a sympathetic case with the potential for a high verdict are unlikely to surrender their claim to a jury trial, and may even try to fight a mandatory arbitration clause. In addition, those cases on a litigation track have options for weeding out the cases with little or no merit (e.g., summary judgement), and extended schedules can create more opportunity and incentive for settlement. What that means is that the cases that do make it all the way to trial are different. By and large, they are probably much better cases with much more at stake.

In that context, it is no surprise that cases in litigation would have a higher plaintiff win rate and higher median damages. That by itself does not mean that juries are per se worse for employers in comparable cases. To get to that question, we need to look at a few other perceived differentiators between juries, judges, and arbitrators.

Should I Avoid Juries Because They’re Too Obsessed with Fairness?

The perception is that, compared to the legally-trained fact finder, juries are likely to approach the case first and foremost as a morality play on whether the employer was fair or not. There is some basis for believing that jurors are more likely to put ethics over the law. In our annual surveys, we have asked over the years the question, “When personal ethics and law conflict with one another, which should you follow?” Typically two-thirds of jurors will respond “the law” while one third will respond “personal ethics.” When we asked that question of arbitrators in 2007, just 17 percent selected ethics, and when we asked it of federal judges in 2008, just 11 percent preferred ethics.

So there is a greater tendency for juries to arrive at a case with a fairness orientation, and that can be magnified by the fact that nearly all jurors are bringing and applying their own experiences as employees and implicitly asking themselves questions like “would my boss have done that?” or “would I have taken the same actions as this employee?” It is a mistake, however, to see juries as the only ones focusing on fairness. When, in 2007, we ran a head-to-head comparision looking at arbitrators’ and jurors’ response to the same case, it was striking that both fact finders mixed fairness in with the law in evaluating the case.

It is also a mistake to think that an emphasis on fairness only works to the employee’s advantage. For example, in a brief focus group that we ran earlier this month, mock jurors responded to an age discrimination scenario by focusing on the company’s right to focus on bottom line results. “The probability of there being some kind of discrimination is real,” as one mock juror noted, “but if the company can prove his performance was not up to standards, that denies his right and puts me in the position where I support the company. Bottom line, businesses are in the business of making money, they have to be.”

Should I Avoid Juries Because They’re Out of Control on Damages?

Another perception, augmented by the data above, is that juries are more attuned to deep pockets and more accepting of extreme damage claims once they reach a conclusion of liability. Certainly, anecdotes do support the conclusion that some juries can be awfully generous. But the claim that juries as a rule are more extreme than the individual legal decision makers (judges and arbitrators) fails to account for the moderating effect of group dynamics.

That is, the perception that juries give high damages is widespread, even among those who serve on juries. When we asked the jury-eligible population in 2007, 36 percent declared jury awards to be “excessively large,” and an additional 23 percent felt they were “large.” That left only a minority of jurors believing that awards are “about right” or “too small.” That distribution nearly guarantees that, even after strikes, there will be some on the panel who are sensitive to exaggerated damages and will act as an anchor to bring damages down.

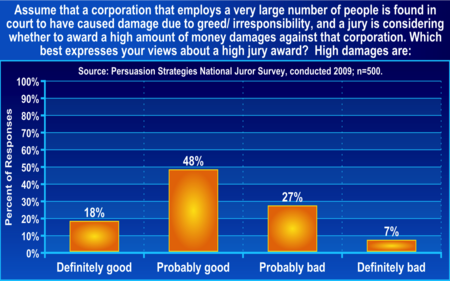

For example, in our 2009 survey, we gave respondents a scenario in which we asked them to presume that a company was liable and acted out of greed, and even in that setting, fully a third felt that “high damages” were probably or definitely bad.

There is also an important difference in what is considered “high.” In our survey, we asked participants to describe an award of $10 million in an industrial accident case and 27 percent of juror-eligibles, versus just 5 percent of arbitrators considered that amount to be “excessively large.” A majority of arbitrators, 53 percent, instead considered that amount to be “about right.” That suggests that those who work in law may simply be desensitized to higher numbers and may be starting out the case with an elevated benchmark.

And there is research to support that tendency. Looking at comparable automobile collision cases that ended up in either arbitration or jury trial Wittman (2003), found that the arbitrators awarded higher damages after controlling for differences within the cases themselves. Applying similar methods to a comparison of juries and judges, two other studies (Clermont & Eisenberg, 1991; Vidmar & Rice, 1992), found again that the judges awarded the higher damages in comparable cases. It is easier for a single decision maker to go to an extreme. If a juror is very liberal on damages, she will probably be checked by someone else on the jury who isn’t. But if a judge or arbitrator is liberal on damages, he will be unchecked. This provides another good reason for providing an alternate anchor by providing your own damages estimate in most cases.

Should I Avoid Juries Because They Have It in for Corporations?

We always hear some gasps and nervous chuckles when we play one particular juror deliberation clip for a defense audience. “I hate large companies,” the juror opines, “I absolutely despise them. I think they are what’s wrong with this country. But they are a necessary evil. Like, our government is Enron, Walmart, pharmaceutical companies. They’ve taken the American dream, smooshed it, drawn a picture of another one and they’re mass selling it to everyone.” That level of anti-corporate attitude is somewhat typical as we’ve written before.

What is generally most surprising to the audiences is that such attitudes aren’t unique to just a small segment of the population, like those manning the “occupy” barricades, but are widely shared. Over the last decade, for example, we have tracked agreement or disagreement with the statement, “If a company could benefit financially by lying, it’s probable that it would do so,” and have consistently found that eight in ten potential jurors will agree with that statement. When we asked that same question of judges, we didn’t find eight out of ten…but we find nearly five in ten (45 percent) agreeing that corporations “probably” lie for money.

So, again, the pattern is that there are some important differences with the jury population, but they aren’t necessarily as extreme as you might expect. Just as it is wise to address fairness as a dimension of your argument with all audiences, it is prudent to assume that there is a baseline level of anti-corporate bias that you face not just in addressing jurors, but when persuading arbitrators and judges as well.

One practical implication of these attitudes, that applies in particular to employment cases, involves the burden of proof. During the employment focus group we ran earlier this month, I asked the group, “Who bears the burden of proof — the employee to prove they were discriminated against, or the company to prove they terminated for legitimate business reasons?” Half the panel got the right answer, but the other half responded that it should be the company, because “it was their choice” to terminate and because they can show “their common practices.” As one mock juror noted, “I think it’s the company’s responsibility to show that [discrimination] could not be what happened.” In other words, they have to rule it out. That may be legally incorrect, but there is a logic to it since the employee generally has less access to the reasons for the decision and the business is, after all, defending its own decision. In most employment cases, defendants are better off acting as though they have the burden of proof, and that applies even when the fact finder is an arbitrator or a judge.

My point is not to suggest that one fact finder is necessarily better than another in all contexts. But the current level of migration to mandatory arbitration by employers reflects a belief that arbitrators are always better, and a closer look reveals that it isn’t so simple. A focus on fairness and a susceptibility to bias can influence all decision makers, and there is at least some chance that the single decision maker is a greater risk than a jury that has to compromise. What is best is a situational analysis in each individual case rather than a blanket preference.

______

Other Posts on Employment Litigation:

- Treat Your Terminations as “For Cause” (Even When They’re “At Will”)

- Take a Note From an Anonymous Law Firm: Don’t Look For Discrimination if You Don’t Intend to Do Anything About It

- Assess Your Juror’s Economic Security: A Vulnerable Juror Can Make for a Vulnerable Defense (Part One)

- In Employment Cases (and All Cases), Keeping it Simple is Smart

______

U.S. Department of Justice (2002). Civil Trial Cases and Verdicts in Large Counties.

Clermont, K.M. (1992). Trial by Jury or Judge: Transcending Empiricism. Cornell Law Faculty Pulbications. Paper 246. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/246

Colvin, A. & Pike, K. (2012). The Impact of Case and Arbitrator Characteristics on Employment Arbitration Outcomes. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Academy of Arbitrators, Minneapolis, MN.

Vidmar, N. & Rice, J. (1992). Assessments of Noneconomic Damage Awards in Medical Negligence: A Comparison of Jurors with Legal Professionals. Iowa Law Review 78.

Wittman, D. (2003). Lay Juries, Professional Arbitrators, and the Arbitrator Selection Hypothesis. American Law and Economics Review 5.