By: Dr. Ken Broda Bahm –

This post is focused on bulking-up your ability to target high-risk jurors and performance enhancing your voir dire. So speaking of steroids, let’s start with Barry Bonds. Jury selection for the perjury trial of the former San Francisco Giants power-hitter, charged with lying to a grand jury over steroid use, starts this week. Prospective jurors will fill out a 19-page questionnaire focusing on the factors that both sides believe should help to reveal bias and guide the process of exercising cause and peremptory challenges. But how reliable is the information underlying these questions? A recent New York Times online article contains a curious contrast of opinions on the question of how tightly San Franciscans will cling to their opinions on Bonds. Howard Varinsky, a Jury consultant, famous for his work in high profile trials like Michael Jackson’s, says “things have changed…” and a lot of people have “grown very ambivalent” on Bonds. Another consultant, Chris St. Hilaire, however says that opinions are likely to have remained very strong: “finding someone who doesn’t have an opinion about Barry Bonds is like finding a cowboy who doesn’t have an opinion about a horse.” So who is right?

According to some recent research (Druckman et al, 2010), the answer would generally depend on how the attitudes were formed in the first place. If they were formed in direct response to new information (called “online processing”), they would be more long-lasting, and if they were formed based on recalled information (called “memory processing”) they would be less durable. But in the case of broad-based attitudes formed as a result of a drawn-out public saga, like the controversies in the run-up to the Bonds trial and most other media-saturated trials, potential jurors are going to have a mix of both attitudes. The specific constellation of attitudes in a case like this is likely to be a mix of long-held memories of Bonds as a star athlete living in combination with newer information about Bonds as a steroid user.

So as with many questions relating to litigation persuasion, the answer is that you need to ask. Instead of relying on general research, intuition, or expectations, you need to conduct specific research on the personalities and issues relating to your case. In the Barry Bonds case, that means taking a step that both sides involved have probably taken: conducting research on community attitudes on Barry Bonds and the issue of steroids in sports to find out the strength and prevalence of attitudes, and most importantly, to find out how those attitudes correlate with a bias for or against Mr. Bonds.

But the answer is not as simple, or at least should not be as simple, as just commissioning a phone survey. Instead, where possible, you should draw upon your pretrial research. To be clear, what I’m not saying is that you should just run a simple mock trial, notice that the handful of women you see (or Hispanics, or red-heads, or whatever) seem to be biased against you, and go on to strike those groups in the actual trial. That approach elevates the inevitable idiosyncrasies you see in a small group project, and it is a mistake. Instead, I’m suggesting an integrated approach using several different research methods and larger sample sizes to support statistically reliable jury selection decisions in those high stakes cases where the resources support it.

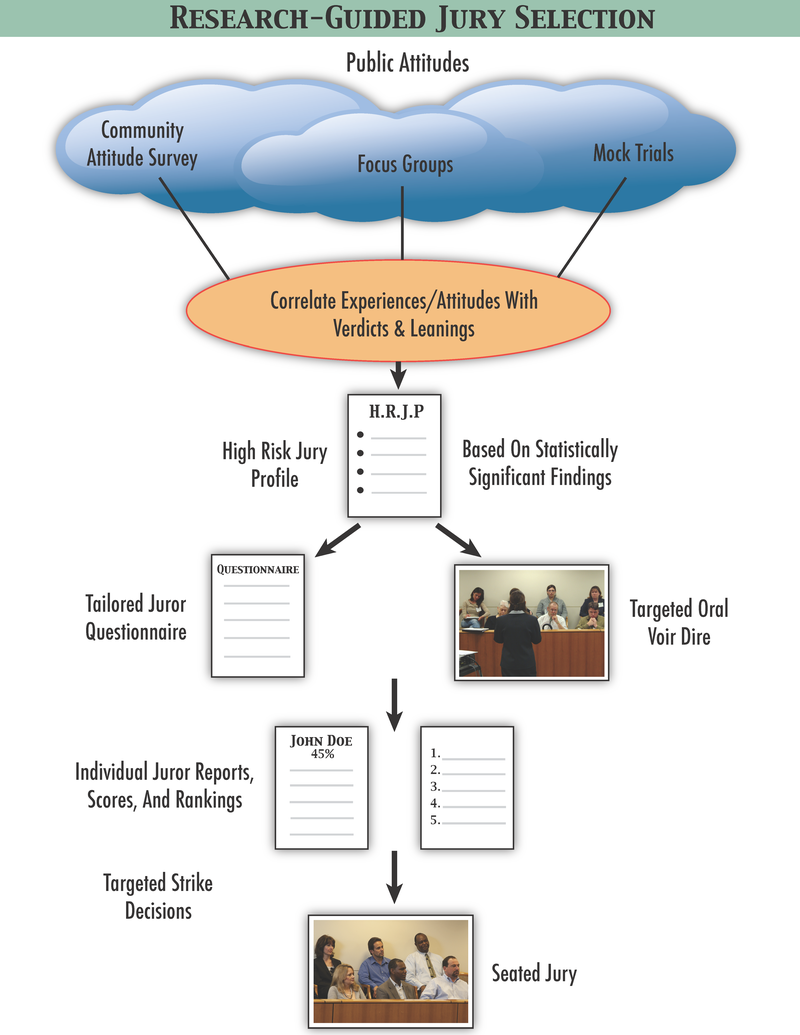

For example, our own work on a recent class action case (summarized in the flow-chart below), started with a very general need to know what citizens in the venue thought about the issues of our case, but ended with jurors selected and strikes exercised based on factors that we knew at the time to be statistically significant predictors of bias against our clients on the most important case issues.

We proceeded in several steps:

Step One: Community Attitude Surveys. We randomly canvassed the venue with sufficient numbers to provide statistical significance, and asked about the issues that we knew would come up in the case. Based on this early research, we designed step two.

Step Two: Small Group Research (focus groups and mock trials). In discovery, when choice of venue was still an issue, we conducted several focus groups in different locations. Later, when the venue was set and discovery was concluded, we conducted mock trials in the venue of choice. In sum, a total of ten mock juries heard this case, and that information supplemented the community survey.

Step Three: A High-Risk Jury Profile. Often profiles of the attitudes and experiences of your most risky jurors (those you want to strike) are based on your own judgment and experience, and there is nothing wrong with that. But in this case, we also had a boatload of data (formed in steps one and two), so we had dozens of factors at this point that we knew, at a level of statistical significance, to be reliable predictors of bias against us. So the profile in this instance was based largely on factors that we had observed, tested, and trusted.

Step Four: Develop Targeted Questions. The written juror questionnaire and oral voir dire strategy can be based on the research findings. For example, at the beginning of our mock trials, participants filled out the questionnaire that would later become the supplemental juror questionnaire used for the actual jurors. Because we knew which questions worked reliably in predicting mock trial leanings, we were able to focus on those questions in assessing the potential trial jurors.

Step Five: Produce Juror Reports and Rankings. Once the questioning strategy was focused on uncovering exactly the variables that we knew to be predictive, the next challenge was to rank each juror based on their answer. We used a program we call JuryNotes in order to record all of the answers (to questionnaires and in-court voir dire), to weight each question based on the strength of the observed relationships, and to create overall scores that pinpointed how much of a threat each potential juror was in relation to the others.

Step Six: Exercise Strikes. The end result of all of this is that you are able to look at each juror, report systematically how bad or good for your case he is, and exercise your strikes accordingly. Of course, the data doesn’t replace everything, and there is always a role for your gut feeling. But the advantage of looking at all the factors, and tracing those factors back to the research that you conducted, is that you are able to base your evaluation on the whole picture and not just react to the last thing the potential juror happened to say.

In the end, I remember the surprised look on opposing counsel’s face, while he flipped through a yellow pad and we peeled off pre-printed individual “report cards” on each venire member, and arranged them in a grid for questioning. Having travelled that path all the way to the final selection, we felt extraordinarily confident about our jury, but the best result came in the end. Not only did our team prevail on all counts, but the judge was heard to remark at a CLE a month or so later, that in his opinion we had “the perfect jury.”

Now, not every case is going to merit or be able to afford this workup for voir dire. But even when it isn’t possible to conduct tailored research for the case, it is nontheless a good idea to target attitudes that we know from national data to correlate with higher-risk in similar cases wherever possible.

To bring it back to Barry Bonds, we have to wonder to what extent the prosecution or defense made use of these tools for the trial starting this week. We can’t know, but based on the fact of a 19-page questionnaire, we can bet that many of these questions are based on more than general interest, and are known to be predictive of bias one way or another. Strikes are often based on general experience and judgment, but whenever they can be based on actual and reliable research findings, that is some serious juice.

______

Related Posts:

Druckman, J., Hennessy, C., St. Charles, K., & Webber, J. (2010). Competing Rhetoric Over Time: Frames Versus Cues The Journal of Politics, 72(01) DOI: 10.1017/S0022381609990521

Druckman, J., Hennessy, C., St. Charles, K., & Webber, J. (2010). Competing Rhetoric Over Time: Frames Versus Cues The Journal of Politics, 72(01) DOI: 10.1017/S0022381609990521

Photo Credit: Andres Rueda, Flickr Creative Commons