By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

Let me start differently in this post, with a ‘Tale of Two Tales.’ Here is tale number one:

First, From the Plaintiff’s Perspective:

It is January, 2010. Brian Starr, a computer storage engineer on contract for GiganTech Industries has come up with a rough design for the UltraDrive, a radical new design for a computer hard drive that will increase storage space and performance while reducing manufacturing costs. Brian is all the more enthusiastic about the idea because his contract with GiganTech grants him a share of royalties from any new product. So he begins work immediately, looking into a path to market.

It is March, 2010. Brian and GiganTech are facing the normal amount of problems in fleshing out a new product. There are many issues to troubleshoot, but they all seem resolvable and it will be worth it in the end.

It is June, 2010. Brian realizes that GiganTech has lost patience with the UltraDrive. He thinks they must have had unrealistic expectations for a quick path to market, because they’re cutting their losses and moving on. Brian Starr’s contract isn’t renewed, and after being told that GiganTech has no plans to ever get UltraDrive to market, he signs a standard form agreeing that he has been paid all he is owed by GiganTech and releasing all future claims against the company.

It is October, 2010. Brian Starr is shocked when GiganTech comes out with a product nearly identical to the UltraDrive and immediately seizes a large share of the market. Brian calculates that, but for the release he signed, his share of royalties would top $3.5 million.

So far, it is a story of dashed expectations and perhaps too much trust. But let’s take another look.

Now, Going Back to Add What the Plaintiff Didn’t Know

It is January, 2010. GiganTech executives are pleased with Starr’s new idea. To hedge their bets, they immediately send the sketches and the specs to one of their subcontractors, Far East Innovations, asking if the idea is feasible or not. They don’t tell Starr about this.

It is March, 2010. Starr is running into trouble designing a manufacturing line. Far East Innovations, however, says that not only is the idea feasible, but they can make it themselves using their existing lines. While a few technical fixes are necessary, Far East is confident they can address them quickly.

It is June, 2010. After thinking it over, GiganTech executives decide to pull the plug on Starr and go with Far East Innovations. Hoping for a big market surprise, they keep everyone in the dark including Starr. The head office decides to end the relationship with Starr and get a release from him so there will be “no strings attached” to the new product. They tell him that GiganTech has no plans to manufacture the product, which is true, but it leaves out the part about Far East’s manufacturing lines.

It is October, 2010. GiganTech launches a product that is a combination of Starr’s idea and Far East’s manufacturing. The company sees record profits. Brian Starr gets nothing.

Now, that is a different kind of story. Instead of too much trust on Starr’s part, we’re talking about fraudulent concealment on GiganTech’s part. Litigators face strategic choices in mapping out their trial stories. One way would be to just walk through the narrative once, sharing everything that happened when it happened. Another way is to tell it twice, as I do above, focusing first only on what the plaintiff knew at the time, and then coming back to fill in what the plaintiff didn’t know at the time and only learned through subsequent events and through discovery. That latter approach of overlapping two stories can have some advantages.

Why Overlap the Stories?

Take the example above. From the plaintiff’s perspective, the central challenge is to address the question, “Why would you sign a release?” That is much more understandable if we’re able to consider it first while standing in the Plaintiff’s shoes, knowing only what he knew at the time. From his perspective, in the summer of 2010, there would be no reason to assert a right to royalties on a project that he had every reason at the time to believe was being shelved.

Beyond this example, there are several situations in trial where advocates will have an interest in reducing the knowledge, power, and responsibility of their own clients. Obviously, jurors will need to understand the whole story in those cases, but if they’re first able to appreciate the story through your client’s eyes, and not from an unrealistic omniscient standpoint, the fact finders are more likely to avoid hindsight and “you should’ve known better” thinking. In those settings, there are a few rules of thumb in telling the story.

1. Avoid the Omniscient Narrator. When you read novels, you know that sometimes you have a narrator who has a ‘God’s eye view’ of everything going on, as captured in a phrase like, “little did he know that the person next to him was a spy!” In other cases, the narrator is a character in the story, bound by the limits of his or her own perspective. We know that when it comes to demonstrative exhibits, the overarching point of view in the omniscient perspective can lead to feelings of greater responsibility, and at times, an unrealistic perception of what one should have known. The same applies to storytelling.

2. Tell the Naive Story First. If the goal is for fact finders to identify with your ‘character’ in the story, then consider establishing that connection by putting your jury in the shoes and behind the eyes of that individual, at least initially. It also helps to add details that will help listeners see the story as you tell it, and that means fleshing it out more fully than I have in the brief examples above. Once you tell the simple and perspective-bound story, then the punch comes from moving to an omniscient mode and letting listeners in on what that party didn’t know at the time and only came to appreciate later.

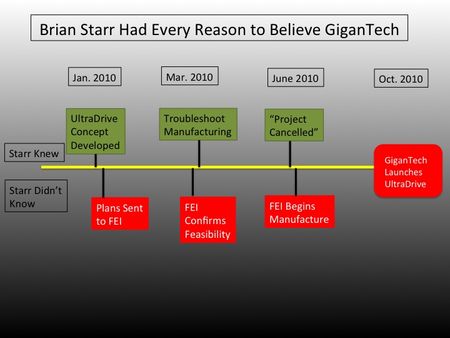

3. Separate the Stories on the Timeline. In telling two different stories, your timeline can often help. Instead of just meshing all of the entries together on one line, regardless of who knew what at the time, you can use the horizontal axis to separate those events. Using the example below, you could first tell the story using the green entries above the line (‘the world as Starr knew it’), then you could go back and add the red entries (‘what Starr didn’t know’) in order to complete the picture.

Other Posts on Story:

- Your Opening: Tell It Like a Story, but Tailor It Like a Strategy

- Find the “Universal Morality” in Your Case Story

- Take a Lesson from the Casey Anthony Verdict: It Is the Story, and Not Just the Evidence

- Don’t Put “Story” on Too High a Pedestal

- Talk to the Eyes: If It Can’t Be Visualized, It’s Not a Story

______

Photo Credit: K. Broda Bahm