By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

My 8-year-0ld daughter is currently obsessed with a game called “Minecraft.” She is using increasing portions of her precious screen time to sign into her “worlds” in order to build and develop elaborate houses and other buildings. As I understand it, the point isn’t to rack up a high score or to “win” anything, it is just to transform a landscape by constructing things. As she describes it, the game seems to appeal to a basic cognitive need: The need to structure. What the game promotes is similar to what the brain wants to do with any new information. The brain’s preference for order suggests that learning something is not based on acquiring new facts in a simple list-like fashion, but in coming up with a system for categorizing those facts. More important than the data, are the “drawers” we keep that data in. As we become an “expert” in any area, we gain more facts, but more importantly, we gain more structures.

It is called the “structure-builder” theory of learning (Gernsbacher, 1997), and based on a recent ScienceDaily release, the perspective posits that “deep comprehension requires a two-step process in which learners must first identify and understand key terms and concepts and then grasp how these pieces fit together into a cohesive framework.” That idea is supported in a recent study on learning published in the Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition (Bui & McDaniel, 2015). Looking at individual differences in the way our minds process learning, the study found that “providing students with illustrative diagrams showing relationships among key concepts to be discussed in a lecture can boost student learning and recall.” This worked for all learners, but particularly for the “low structure-builders” who did not take naturally to the process of seeing those relationships on their own. This research carries a high practical value, not just to lecturers, but to litigators. This post will provide a quick summary of the research and offer some simple advice on this way of improving courtroom teaching and persuasion.

What Is ‘Structure-Building’ and Why Do Diagrams Help?

A team from Washington University’s psychology department, Dung Bui and Mark McDaniel, conducted the study using 144 college undergraduates who had no prior mechanical experience. Those participants listened to spoken explanations focusing on the key components of an automobile’s braking system and how they work together to slow a car. As an aid to the lecture, some were given a blank piece of note paper, others received an outline of the lecture, and a third group saw a diagram showing the relationship of the key ideas. The participants were also measured in advance on their aptitude for structure building.

The study showed that those seeing the diagram performed substantially better than those receiving an outline or nothing. As expected, high structure builders needed this aid much less, but they still did better when armed with the diagram. For the low structure-builders, however, the assistance provided by the diagram was critical. As Mark McDaniel notes, “Some students are very good at building these mental frameworks on their own, but others struggle with the process.” Providing a conceptual diagram linking the key concepts is a way of saying, “here’s a mental framework you can adopt.” It helps learners in understanding the importance of the information as well as the relationship among discrete facts.

What Does It Have to Do with Litigation?

This isn’t just a lesson for lecturers in scholastic contexts. The “lectures” that emerge from either the podium or the witness box in a courtroom suffer similar challenges: Jurors need to understand it before they can be persuaded by it, and understanding requires developing a framework or a structure for the information.

And this is where lawyers might fail to appreciate the need. I think it is safe to say that lawyers are high structure-builders. If they weren’t, they probably wouldn’t have made it through law school. Based on training and daily experience, lawyers listen with an analytical ear, structuring and categorizing information as they hear it. Jurors, however, are a lot more diverse: Some are high structure builders and some are low structure-builders. Broadly convincing the whole group means reaching both. That means the case will sometimes depend on making those who don’t think like lawyers adopt that ability at least temporarily.

The need for structure building is clear in the courtroom. Jurors need to not just take in information, but to see the relationship of one piece of evidence to the next, and to understand the implications. They need to understand the answer to questions like, “If this individual fact is true, then how does that support this party’s overall point?” Lawyers can too often make the mistake of taking those connections for granted and not making it explicit. Jurors need not, “just the facts, Ma’am,” they also need the categories and connections that help them get the point and follow the whole story.

So here’s a reminder for lawyers: Make those connections clear, blatant, obvious, explicit, and repeated. One way to do that is to provide a diagram prior to the evidence. As McDaniel notes, “The key takeaway here is that providing learners with supportive material in advance of the lecture helps them build a comprehensive model of how each part of the system relates to the next.”

An Example, Please?

Sure. Based on the image and the title for this post, one concern I had was that readers might think that this is a post about construction litigation. Of course, it’s a post about all trial messages, but I’ll meet any such reader halfway and make my example focus on construction litigation.

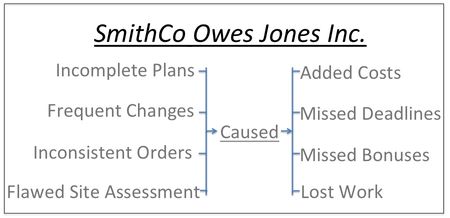

So imagine that the plaintiff general contractor (Jones Inc.) is suing the owner/developer (SmithCo) for losses caused by several sources of delay — a common scenario. A very simple conceptual diagram for the GC’s arguments might look something like this:

Of course, that is a very basic distillation of the company’s core message, but it also means that it is very easy to create. It could even be written onto a flip chart during opening statement, and then left up. That way, when jurors are hearing the attorney move through the necessary minutiae on dates, deadlines, plans, bills, and change orders, they have that clear visual reminder of how it all fits together.

______

Other Posts on Organization:

- Chunk Your Trial Message

- Close Your Case By Walking Through the Decision and Verdict Form (Another Note on the John Edwards Trial)

- When You Think “Story” Think “Structure”

______

Dung C. Bui, Mark A. McDaniel (2015). Enhancing learning during lecture note-taking using outlines and illustrative diagrams. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 2015; 4 (2): 129 DOI: 10.1016/j.jarmac.2015.03.002

Gernsbacher, M. A. (1997). Two decades of structure building. Discourse processes, 23(3), 265-304.

Image credit: 123rf.com, used under license