By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

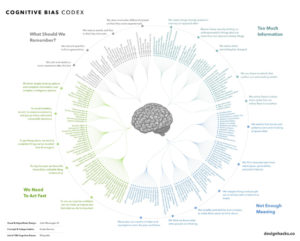

The law expects legal decision making to work like a smooth and well-oiled machine. But as any experienced legal persuader knows, there is sand in those gears. That sand takes the form of cognitive biases: mental shortcuts or heuristics. They’re not necessarily mistakes, but factors that make legal decision making from a judge or jury less linear and logical than the legal model might presume. I wrote last year on advantages of knowing your cognitive biases based on a newly-published list of such biases. To advance the taxonomy, Jeff Desjardins of the media website Visual Capitalist has more recently developed a handy image: “Every Single Cognitive Bias in One Infographic.” The list is detailed, including fully 188 known and documented biases. The infographic, together with a brief explanation, is available at the link above, and a high-resolution version is also available.

The Visual Capitalist illustration follows the same approach as the “Cognitive Bias Cheat Sheet” I wrote about earlier, but adds a couple of levels of organization that helps to show the relationships between the biases, and because you aren’t really going to memorize 188 biases, it emphasizes the broader concepts involved. The outer ring lists these main principles focusing on selective memory, too much information, not enough meaning, and a need to act fast. The next inner circle lists 20 general tendencies, like “We edit and reinforce some memories after the fact” and “we simplify probabilities and numbers to make them easier to talk about,” each covering around 5 to 20 cognitive biases. In this post, I’ll walk through those 20 forms of cognitive bias to briefly highlight the roles they play in legal persuasion.

Here is the infographic:

(click for a bigger version)

This blog post isn’t the place to cover each and every bias, but let’s at least address those broad categories in the middle ring and what they might mean in litigation.

Too Much Information

We notice things already primed in memory or repeated often

This is why litigators introduce priming topics in voir dire, repeat themselves often, and give special attention to what comes first and last. The ‘availability heuristic” suggests that the more top-of-mind it is, the more it is likely to influence our decision making.

Bizarre, funny, visually-striking, or anthropomorphic things stick out more than non-bizarre/unfunny things

Focus on the unexpected, because that is what stands out. An original figure of speech, or a surprising story or image can help to capture and cement jury attention.

We notice when something has changed

We are drawn to variety, whether that applies to the speaking style or the facts. A central principle in graphic design is not to make everything the same, but to design so that, for example, the key moment or the ‘before versus after’ contrast stands out in a timeline.

We are drawn to details that confirm our existing beliefs

We tend to believe that we are right, so we tend to notice, remember, understand, and use the information that confirms those beliefs rather than refutes them. That is why it is key to account for confirmation bias by knowing what your judge or jury already believes and adapting your arguments to those beliefs.

We notice flaws in others more easily than we notice flaws in ourselves

The fault that we miss most often in ourselves is bias itself. So in addition to thinking that we’re right, we also tend to (paradoxically) think that we’re unbiased. This ‘blind spot,’ of course, limits your ability to trust in your panelists’ promises to be fair in voir dire, and suggests that you need strategic and sometimes indirect ways of asking about bias.

Not Enough Meaning

We tend to find stories and patterns even when looking at sparse data

Our brains are hard-wired for imposing order. The “Rorschach” test where you look at inkblots is a good example: It’s a random shape, of course, but we still want to see it as an elephant or a tree. Jurors will also inevitably look for and find patterns in the facts and the behavior or the parties. If you don’t take control of telling them a story, they’ll find one of their own.

We fill in characteristics from stereotypes, generalities, and prior histories

Jurors tend to prefer low-effort thinking if they can get away with it. That means relying on stereotypes and generalizations. It means that mental shortcuts (heuristics), like assuming that a defendant is probably guilty or a big company is probably dishonest, are often the go-to habit for jurors.

We imagine things and people we’re familiar with or fond of as better

The more we know something, the more we tend to trust it. That is why it is often a good idea for attorneys and witnesses to share some personal detail. Even when that detail isn’t relevant to the case or to the testimony, the greater familiarity helps to convey greater credibility.

We simplify probabilities and numbers to make them easier to think about

People don’t tend to comprehend probabilities very well, and will resist complex quantitative exercises as well. That’s why, on both chance and numbers, we tend to look for shortcuts. One such shortcut is the “anchoring effect.” If you throw out a number, there is a very good chance that it will at least serve as a starting point in any discussion.

We think we know what other people are thinking

Part of our interactions with others include the “theory of mind,” by which we think about and form theories about the internal motivations of other people. When jurors search for reasons to place blame in either criminal or civil cases, those attributed motives can be as important or more important than actions.

We project our current mindset and assumptions onto the past and future

It is hard to step outside of a current mindset, or to set aside what we now know or believe to be true. So we tend to take that current knowledge and use it to evaluate past actions (the danger that’s clear in hindsight should have been clear at the time), and to project it into the future (the patterns that we’ve seen from parties in the past are expected to continue).

We Need to Act Fast

To act, we must be confident we can make an impact and feel what we do is important

Jurors and judges aren’t fact-finding machines, they are motivated to find meaning in what they’re deciding. That means that a decision is always going to be tied in some way to values. In rendering a decision, they’re not just applying the law to the facts, they’re striking a blow for justice, fairness, consistency, or some other social value that carries an impact.

To stay focused, we favor the immediate, relatable thing in front of us

We favor what is immediate over what is abstract. That makes us prone to personalize notions of danger and risk, and that is the mental habit that makes The Reptile strategy possible. Jurors look for a connection between themselves and the case that they’re hearing.

To get things done, we tend to complete things we’ve invested time and energy in

Just like a gambler becomes more invested after losses (because they want to end up as a winner), people can be motivated by sunk costs. That can explain why jurors are often deeply disappointed when a case settles mid-trial, but it can also explain why a litigation team continues to dig in even past the point where it would be wiser to settle the case.

To avoid mistakes, we aim to preserve autonomy and group status, and avoid irreversible decisions

There can be a tendency to favor the decision that’s already been made, and that means leaning toward whatever might be perceived as the status quo. Particularly for jurors high in authoritarianism, that can mean favoring the party that appears to have the greater social power and opposing actions or decisions that would seem to be a threat to order.

We favor simple-looking options and complete information over complex-ambiguous options

The simpler something is, the more it is likely to strike jurors as true, and the more involved and complicated it is, the more they’re likely to be skeptical of it. That adds a further imperative to trial lawyers to shed unnecessary detail and to boil the case, including expert testimony, down to the essentials.

We Streamline Our Memories

We edit and reinforce some memories after the fact

Focusing on what we remember changes our memories. That is true of eye-witnesses since memories are always, to some extent, reconstructions. It is also true of jurors. We trust that they’ll remember and use what they heard during trial, but they’ll also apply a strong filter to those recollections, exaggerating some elements and downplaying or missing others.

We discard specifics to form generalities

We naturally search for types: What type of person is this? What form of action was this? What kind of case is this? Stereotypes are inevitable in the act of perceiving and forming judgments. Awareness of those stereotypes, however, is something that can help in hearing cases and also in selecting juries.

We reduce events and lists to their key elements

While we like to think of jurors accumulating information as they hear more and more during a trial, it is also true that, just in the act of sense-making, they are continually shedding information. In a long examination, every question is going to have a purpose, but it pays to ask yourself, “What are the two or three questions that I really want this jury to remember?”

We store memories differently based on how they were experienced

How we receive information can have a big effect on how we retain that information. That is why employing strategic structure, including dividing a story into chunks or chapters, is so critical. Is it also why the first or the last item presented takes on special importance, highlighting why attorneys need to think carefully about introductions and conclusions.

Thankfully, you don’t need to memorize all 188 cognitive biases on the wheel. But, when analyzing judges, jurors, or any audience, it helps to keep these general and reliable tendencies in mind.

______

Other Posts on Cognitive Bias:

- Know Your Cognitive Biases

- Don’t Fool Yourself on the Advantages of Intelligence

- Know (and Use) the Cognitive Biases of Mediation

______

Image credit: Edited detail from Cognitive Bias Codex: http://www.visualcapitalist.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/cognitive-bias-infographic.html