By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm –

The term “woodshedding” as applied to a witness has a colorful history, starting with the notoriety of a small structure just outside the colonial courthouse in White Plains, New York, where attorneys would meet with witnesses just before coming in to court. As used today, “woodshedding” basically means telling witnesses, fact or expert, exactly what to say and exerting enough personal control over the witnesses to make sure that they say it. It is a bad idea for several reasons ranging from ethical, to practical, to persuasive. While most attorneys will avoid the absolute extreme of witness ventriloquism, it is best to think of a continuum with “just tell the truth,” on one end, and “repeat after me” on the other. While members of the public, including jurors, might wish for all witnesses to be on the former end of the scale, that leaves out several important and meaningful components of testimony. Litigators and other students of communication know that within the range of truthful testimony, there are better and worse ways to explain, more and less effective ways to give and withhold emphasis, and persuasive and unpersuasive ways to simply clothe ideas in words. So in all of those areas, “just tell the truth,” isn’t enough help.

But the other end of the spectrum, where truthfully more than a few attorneys live, isn’t the best answer either. The problem with an overly heavy hand in witness control, beyond suborning perjury in the worst case, is that you are draining credibility from your witness. You may gain predictability over what your witness says, but only at the cost of your witness feeling and acting less confident and less believable. And an effective cross can quite often expose and undermine even the most extensively woodshedded witness.

One of the most infamous examples of woodshedding was uncovered when a first year associate of a Dallas plaintiffs’ firm inadvertently disclosed what has come to be known as the “script memo.” Entitled, “Preparing for Your Deposition,” the twenty-page document contains detailed instructions on what to say and what not to say to asbestos plaintiffs:

“You will be asked if you ever saw any WARNING labels on containers of asbestos. It is important to maintain that you NEVER saw any labels on asbestos products that said WARNING or DANGER. . . . Do NOT mention product names that are not listed on your Work History Sheets. The defense attorneys will jump at a chance to blame your asbestos exposure on companies that were not sued in your case. Do NOT say you saw more of one brand than another, or that one brand was more commonly used than another. . . . Keep in mind that these [defense] attorneys are very young and WERE NOT PRESENT at the jobsites you worked at. They have NO RECORDS to tell them what products were used on a particular job, even if they act like they do. . .”

That level of instruction is obviously impermissible, since the focus is not on making truthful testimony more clear, understandable, or influential, but on creating and protecting a particular “truth.”

So where does effectiveness lie? True to Aristotle’s Golden Mean, it is closer to the middle of that spectrum between “just tell the truth,” and “repeat after me.” Prepare your witnesses in a way that informs them and respects their autonomy. Don’t put words in their mouth, but make sure they have a good understanding of both the matter of testimony (key issues, likely areas of questioning, goals of the adversary, etc.), as well as the manner of testimony (strategic and truthful response, combined with effective verbal and nonverbal communication).

In my experience, the best way to prepare a witness on difficult substantive testimony is for the attorney, the witness, and a consultant to sit down together and walk through both direct and cross. Instead of talking generally about the content or engaging in free-form practice, however, it makes sense to use some tools to keep it organized and memorable for the witness. I like to create a “witness plan” in order to add structure and emphasis to the witness’s testimony. It can be done on paper, on a flip chart, or – best of all – on a laptop connected to a projector. Depending on your confidentiality concerns, it can be saved, or it can be unsaved and exist ephemerally only during the prep session itself, like writing on a chalkboard. Focusing on both questions and answers in direct, the goal is to capture main ideas, not necessarily language, and to serve as a reference point for the witness.

Importantly, this is prepared with the witness, and not for the witness. What separates an effective “witness plan” from a “script memo” is that it is a distilled version of the witness’s own words, together with feedback and reinforcement provided by attorneys and consultants.

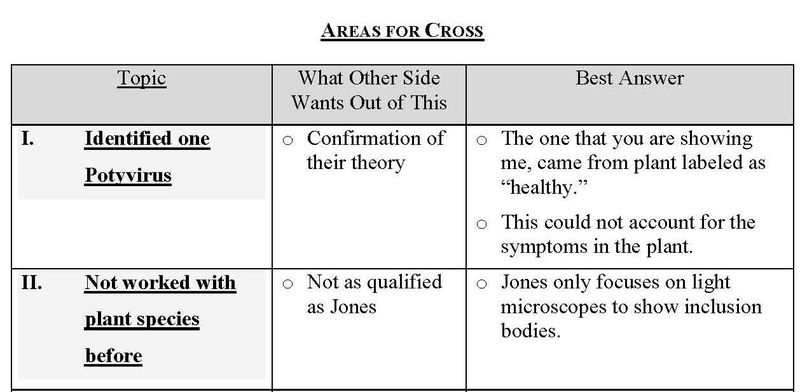

In deposition or cross, of course, it is the opposing counsel who picks the structure and the questions. But you can still use an outlining approach to help the witness prepare for the content. One tool we’ve used for focusing both the witness and our own client attorneys is to think of three dimensions regarding the questions our witness could be asked:

1) On what topics or areas will they be questioned?

2) What are the opposition’s target outcomes? What will they want the jury or decision-maker to take away from their questioning in this area? We find that it is much better to think in terms of opposition target outcomes, which can be predicted, rather than thinking in terms of individual questions which often can’t be predicted.

3) On each of the opposition’s targets, what is the best answer that the facts allow?

Arranged on a simple grid, it looks like this:d

This is best handled as a table that can be updated live during the preparation session by the witness, the attorney, or the consultant, as concerns emerge and as you as a group reach conclusions that you want to record regarding the best answer on each point.

The difference between this and woodshedding is a critical one. Woodshedding refers to the unethical act of telling a witness exactly what to say. That act is distinct, however, from the responsible act of witness preparation, which includes the act of providing witnesses with feedback on where their answers are clear or unclear, responsive or unresponsive, compelling or forgetable. Attorneys and consultants are most effective not when they are coaching a particular answer, but when they are listening and selectively reinforcing what a witness is saying, and telling them what works. But let the witness answer first, and let the words of the witness frame and structure the testimony plan. That not only keeps you honest, it also boosts the witness’s confidence, and keeps you both out of the woodshed.

______

Related Posts:

______

Photo Credit: Number Six (bill lapp), Flickr Creative Commons