By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

Two rival narratives are currently battling it out in a Boston courtroom in the Tarek Mehanna case. The prosecutor’s story involves the spectre of homegrown terror, narrowly averted before anyone was harmed. The defense story involves an individual prosecuted for expressing opinions and for refusing to become an informant for the FBI. A key issue in the case involves the intent of some actions that would otherwise be legal. The Defendant, an American citizen of Egyptian descent from an affluent Boston suburb, is accused of acting as a mouthpiece for Al Qaeda by translating a variety of documents from Arabic into English, such as a manual entitled “39 Ways to Serve and Participate in Jihad,” which appears to be all over the internet.

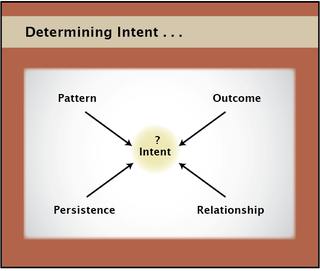

My colleague in Boston, Edward Schwartz, has blogged on this case, most recently focusing on the many “interpretive questions jurors are asked to resolve.” This post takes a closer look at just one of these questions: the dimension of intent that separates legal activity from illegal activity. How do jurors and other fact-finders assess the fundamentally unknowable “black box” of human motivation, and reason from behavior to attributed intent? Based on some research and experience, as well as the example of the Mehanna case, I recommend a four-part model for communicating about intent in civil and criminal trials.

Dr. Schwartz and other legal experts have raised a number of important questions about the case: “At what point does an individual’s behavior, conversations and views amount to “material support” for a terrorist group? When does speech become an instrument to promote terror or recruit for jihad? And when can or should authorities move against someone who is allegedly engaged in “pre-terrorist” activity?” At least partially, the question is whether the Al Qaeda translations that Mehanna posted to his website constitute speech protected by the First Amendment, or whether they constitute material aid to a terrorist organization is a question of intent. Based on standards proposed in the case, the speech itself is protected, unless it aims “to incite or produce imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”

Intent matters in a great many cases. In addition to the concept of Mens Rea, or criminal intent, required to sustain typical criminal charges, there is also intent required in a number of civil contexts: fraud and willfulness for example. Even where intent isn’t an element, jurors and judges tend to look for it anyway, because motive is a fundamental part of any story. The observation of mock jurors in deliberation, for example, shows that even in simple negligence cases that lack intent as a relevant element, hours will be spent discussing why the parties acted as they did.

In the courtroom, motive can be demonstrated through admission. But barring that, the defendant’s state of mind cannot be assessed directly and must be instead inferred from behavior. One philosophically inclined judge described the route to intent as follows: “Intent, as used in ordinary language, is thought to refer to a subjective phenomenon that takes place inside people’s heads. In fact, however, the word ‘intent’ is really shorthand for a complicated series of inferences, all of which are rooted in tangible manifestations of behavior. We need not concern ourselves with the question of whether mental states actually exist, as an ontological matter” (FDIC v. St. Paul Fire & Marine Ins. Co., 942 F.2d 1032, 1035). In other words, while intent as a mental state may be a black box, it reduces to things that we can actually observe.

The research tends to agree. One study (Dennison & Thomson, 2002) is entitled “Identifying Stalking: The Relevance of Intent in Commonsense Reasoning.” In some ways, stalking is a parallel situation where otherwise legal activities (for example, making a phone call, visiting a restaurant, waiting outside someone’s home) are transformed though behavioral context into something illegal. Based on the opinions of the Australian public, the researchers found that in addition to declared intent, several other factors mattered to participants’ ability to define the behavior as stalking. These included the pattern, the persistence, the relationship, and the outcome of the actions. Putting these factors together and applying them to the Mehanna case, intent looks something like this:

1. Pattern. To what extent does the activity fit with the individual’s past behavior? The closer the fit, the more intentional it is likely to be perceived. In Tarek Mehanna’s case, the Defense is likely to emphasize that an intent to aid terrorism doesn’t fit the pattern of someone who served as a community leader and holds an advanced degree in pharmacology. On the other hand, the prosecution will stress that his translation activities are not the only crimes Mehanna is accused of, because he also sought (unsuccessfully) to join a Jihad training camp in Yemen and discussed an attack on an American shopping mall.

2. Outcome. What happened as a result of the individual’s activities? Though it isn’t necessarily a logical inference, the worse the outcome is, the more likely we are to see it as intentional. Based on the “Just World Hypothesis,” we want to believe that tragedies don’t just happen by accident. In the Tarek Mehanna case, the Defense will focus on the absence of evident harm: no attacks, no deaths, just words. The prosecution, for its part, will focus on the harm that might have been, while also invoking events like the Fort Hood shooting in 2009, where a U.S. Army psychiatrist killed thirteen in the name of Jihad.

3. Persistence. How habitual and repeated were the individual’s actions? Naturally enough, the more we persist in a behavior, the more it is likely to be viewed as intentional. In this context, Tarek Mehanna’s defense is likely to emphasize the lack of persistence in the alleged attempts to receive terrorism training and to discuss an attack on a shopping mall, pointing out that both were fleeting ideas that were quickly abandoned. The prosecution, on the other hand, will tell a longer story of increasing radicalization, starting with words, and then transitioning into attempted actions.

4. Relationship. What is the relationship between the individual and the intended target? We will interpret actions consistent with what we believe to be the nature of the relationship. In the case of stalking, for example, a spurned boyfriend is more likely than a stranger to be considered a stalker, even when engaging in the same behaviors. In Tarek Mehanna’s case, the Defense will point out that, even as he opposed the Iraq war and a number of other U.S. policies, Mehanna was deeply involved in the community and anything but the “disturbed loner” that we might associate with terrorist involvement. For the prosecution, though, the translations themselves, with chapter titles like “Have Enmity Towards the Disbelievers and Hate Them” and “Train with Weapons and Learn How to Shoot” are likely to provide a compelling window into that intended relationship.

The trial, occurring over the coming month, is likely to provide an interesting case study in how inent is operationalized and how jurors grapple with the delicate question of when speech makes the transition from opinion to incitement. It is a trial worth following.

______

Related Posts:

- That’s Right, The Women Are Smarter: Pay Attention to Your Jury’s Social Intelligence

- Keep Your Burden of Proof in Your Back Pocket

- Understand Juror Bias, But Bet On The Evidence

______

Dennison SM, & Thomson DM (2002). Identifying stalking: the relevance of intent in commonsense reasoning. Law and human behavior, 26(5), 543-61 PMID: 12412497

Dennison SM, & Thomson DM (2002). Identifying stalking: the relevance of intent in commonsense reasoning. Law and human behavior, 26(5), 543-61 PMID: 12412497

Photo Credit: raymaclean, Flickr Creative Commons