By: Dr. Ken Broda Bahm –

We’ve now been using the phrase “the vanishing jury trial,” for almost a decade, and the decline continues. The days when experienced lawyers could count on finding themselves in front of a jury several times a month are gone, as today’s cases are increasingly resolved by judges, mediators, arbitrators, and other routes to settlement. Even among the best, years can go by in between trials.

This decline in the American trial isn’t just a pining for ‘the good old days,’ but a real and continued trend observed in the research. Joseph Anderson (2010) is a U.S. District Court Judge in South Carolina who has recently combed through state and federal data to document the trend. His article, “Where Have You Gone, Spot Mozingo?’ is named for a legendary South Carolina attorney who tried more than 600 cases, before dying…at the age of fifty-nine! That level of experience has, by all accounts, simply been lost within our system. The keystone work on this issue (Galanter, 2004) is a comprehensive study of trial frequency across the system of American courts, and it notes the following sobering facts:

- In 1938, close to one in five cases were terminated with a trial. Now it is fewer than one in fifty.

- The trend is largely the same whether you are looking at state versus federal, civil versus criminal, or even bench versus jury trial.

- Trials have declined both in absolute numbers, as well as in percentages.

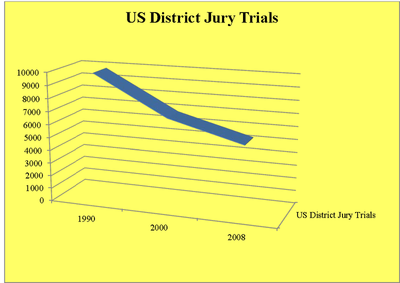

In addition, it isn’t just a long-term historic trend that we are witnessing, but a phenomenon that has continued and increased in recent years. According to data reported in a recent USA Today article, the number of civil and criminal jury trials in U.S. District Court is in steep decline, from a total of 9,844 in 1990 to 5,325 in 2008.

Analysts are nearly uniform in believing that this trend-line will continue, even becoming steeper over time. Why? Two main reasons: One, as fewer cases end up going to trial, the litigant has fewer comparable examples and benchmarks drawn from trial outcomes that would support a realistic case assessment; and two, the less frequent the trial, the greater the proportion of trial lawyers who rarely see trial. As a result, there is a self-fulfilling prophesy and settlement seems like the safest option.

Obviously, this isn’t a one-sided coin, and as we’ve written before, based on a realistic risk assessment by both sides, settlement is often the right way to go. The time and money involved in taking a case all the way to verdict and through appeals can provide good reasons to celebrate the relative infrequency of jury trials. If justice can be done more quickly and cheaply, then so much the better. However, there are some very real effects that a diminishing trial will have on litigants. For example, Judge Anderson has noted a decrease in the trial skills of the attorneys who appear before him as trials become less frequent. Skills atrophy, and attorneys tend to fall in love with discovery, because that is the part of the process they know best.

So what should litigators do to adapt to this new reality? Let me suggest five things.

1. Don’t settle for the wrong reasons. If your preference for alternate dispute resolution is based on the belief that arbitrators, for example, are likely to be more defense friendly, and more conservative on damages, that may be a flawed assumption. One researcher (Wittman, 2003), for example, examined 9 years of comparable cases heard by arbitrators and juries in order to compare the outcomes and, consistent with past research, found non-jury decision-makers, and arbitrators in particular, were more likely to side with the plaintiff. And if it is the time savings that you are after, you should know about a recent comprehensive study (Heise, 2008) showing that ADR did increase the chances for settlement, but did not decrease the overall disposition time.

2. Don’t skimp on preparation for any trial. Galenter, for example, noted the trend that as trials become less frequent, those disputes that do end up going the distance are on average more complex, longer, and higher stakes. That, combined with the decreased trial time experienced by most attorneys, means that you have every reason to use every tool in the box (focus groups and mock trials, systematic jury selection, witness preparation, etc.), when trial looks immanent, or when you need a reality check for settlment purposes. One other advantage: more than one of our clients has noted, at the end of a research day that the mock trial provides nearly the same thrill as a real trial. But even more, it provides experience.

3. Treat bench trials and ADR with the same care that you would give a jury. Granted, there are some approaches that you would save for a lay audience and not offer a legally trained mind. But never accept a message that is less organized, less visual, less rhetorically compelling because it is “just an arbitration.” As the former federal judge and current arbitrator, James Carrigan, put it to us: “My impression is that lawyers do not prepare nearly as well for a trial before arbitrators as they do for a trial before court…. Some lawyers think anything goes: Just back the truck up, dump it all on the arbitrators and let them flip a coin.” Whatever the audience, at the end of the day, it is still a battle of persuasion.

4. Don’t forget about the associates. An entire generation of young, bright, legal minds has recently emerged from law school chomping at the bit for trial experience, only to find that the relatively few trials in the offing are being captained by the more senior members of the firm. Anecdotally, it seems that too many in that generation has tried for a few years, then either moved in-house or resigned themselves, for now, to a life of pleadings, briefs, and occasional depositions. To minimize that loss of personnel and motivation, firms should focus on the types of experiences they are giving associations, devote serious resources to trial and pretrial advocacy training programs, and promote options for hands-on trial experience for associates as often as possible.

5. Consider opportunities for public interest law. For many, the idea of helping others was a big part of the reason to go to law school. If after graduation, the demands of billable hour production gave you a good reason to set those dreams aside, then at present, the practical effects of the vanishing trial give you a good reason to bring them back. Firms that take on pro bono litigation, run legal aid clinics, or allow attorneys ‘time off’ to work in public defender or D.A.’s offices are not only creating a social good, but they are also helping to maintain the practical skills of their attorneys.

None of these are new ideas, but the waning of the jury trial makes them increasingly important for litigators to seriously examine. Trials are becoming less frequent, but the need for experience and effectiveness in the courtroom remains.

Anderson, Joseph F. (2010). Where Have You Gone, Spot Mozingo? A Trial Judge’s Lament over the Decline of the Civil Jury Trial. The Federal Courts Law Review, 4 (1), 99-120

Anderson, Joseph F. (2010). Where Have You Gone, Spot Mozingo? A Trial Judge’s Lament over the Decline of the Civil Jury Trial. The Federal Courts Law Review, 4 (1), 99-120

Galanter, M. (2004). The Vanishing Trial: An Examination of Trials and Related Matters in Federal and State Courts Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 1 (3), 459-570 DOI: 10.1111/j.1740-1461.2004.00014.x

Heise, Michael (2008). Why ADR Programs Aren’t More Appealing: An Empirical Perspective. Cornell Law Faculty Working Papers, 51

Wittman, D. (2003). Lay Juries, Professional Arbitrators, and the Arbitrator Selection Hypothesis American Law and Economics Association, 5 (1), 61-93 DOI: 10.1093/aler/5.1.61

Image Credit: chrisdlugosz, Flickr Creative Commons