by Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

One way to stir up a controversy is to talk about the social expectations that apply to female litigators. The ABA Journal recently played host to that discussion after an article by Debra Cassens Weiss on showing anger in the courtroom quoted an essay in The Atlantic by former pubic defender and current law professor at the University of San Francisco, Lara Bazelon. Based on a review of the literature and interviews with many female trial lawyers, Ms. Bazelon shares her belief that a narrower range of acceptability actively limits what she can teach her female students in law school. Drawing from her own experience, she notes, “My supervisors also reminded me to smile as often as possible in order to counteract the impression that my resting facial expression was too severe. I even had to police my tone of voice. When challenging a hostile witness, I learned to take a ‘more in sorrow than in anger’ approach.”

This discussion led to an emphatic response from Cris Arguedas, a defense attorney in a number of high profile matters including Barry Bonds’ perjury trial in San Francisco. She argues that, rather than limiting themselves based on perceived expectations, female litigators need to employ the full range of delivery, including anger depending on the situation. “A skilled examiner must be able to use all the tools.” Differing expectations on anger is, of course, just one aspect of the context a female attorney faces, but it is one of the more salient distinctions, and one that has seen recent relevant research. As it regards acceptable expressions of anger, I believe that the exchange highlights two separate questions: One, “Are there differences in the latitude of social acceptance for female attorneys?” and two, “If so, does that mean that female attorneys should hold back?” I think the answers are, respectively, “Yes, to some extent,” and “No, not necessarily.” I’ll briefly unpack both of those in this post.

The Research: Anger Helps the Male Attorney, Hurts the Female Attorney

Writing about perceived differences in the acceptability of assertiveness by gender, Ms. Bazelon notes in her article, “This isn’t just dated wisdom passed down from a more conservative era. Social science research has demonstrated that when female attorneys show emotions like indignation, impatience, or anger, jurors may see them as shrill, irrational, and unpleasant.” On that score, she is right.

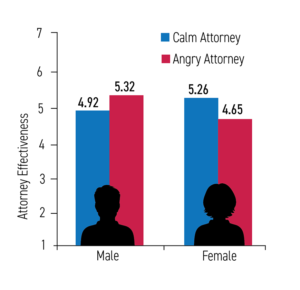

A just-released study published in Law and Human Behavior (Salerno et al., 2018) underscores that point. Researchers from Arizona State University looked at in-court expressions of anger by attorneys and found, “when expressing anger relative to when calm, female attorneys were seen as significantly less effective, while angry male attorneys were seen as significantly more effective.”

One Implication: The Difference Isn’t Tremendous

The difference between men and women represented in the chart above is statistically significant. And, of course, it is also notable that the directions are reversed for male and female attorneys: Consistent with the perceptions and the experiences Ms. Bazelon shares, expressed anger helps male lawyers and hurts female lawyers.

But it is also worth noting that the difference isn’t overwhelming. It likely reflects real differences in social expectations, but that doesn’t mean that women are uniformly punished for expressing anger, and it certainly doesn’t mean that Ms. Arguedas is wrong to show anger when she thinks the situation in the courtroom demands it. One can’t run a study on each individual, and it stands to reason that there are high levels of individual difference regarding the latitude of what one can get away with in court.

Another Implication: What’s Measured Is really Acceptance

In the study quoted above, the dependent variable was broadly labeled “effectiveness,” but was measured through asking research participants about positive or negative inferences (e.g., “strong” or “shrill”), and also through asking participants whether they would hire the attorney they saw on video. Of course, there’s a business development implication there for female attorneys if people say they’re less likely to hire the angry ones, but neither of these measures looks at whether the anger increases or decreases one’s ability to persuade in a given case.

For example, in the response article in the ABA Journal, Ms. Arguedas notes, “even the jurors who don’t like the aggression will get over it,” and she quotes one juror commenting on her cross-examination style post-trial, “I thought you were a bitch, but that witness was a liar.” The social expectation doesn’t necessarily negate the effectiveness.

Final Implication: Comfort Matters

It is critical to filter these results through the eye of the beholder. The article exchange between Ms. Bazelon and Ms. Arguedas actually provides one window into a personality difference that likely plays an important role in mediating the individual effectiveness of anger as a technique. In the Atlantic article, Ms. Bazelon makes clear that she has spent her life trying to avoid emotional expression. “When I got angry,” she writes, “I had to stifle that feeling.” She notes that she tells her students, “adhering to biased expectations and letting slights roll off their back may be the most effective way to advance the interests of their clients in courtrooms that so faithfully reflect the sexism of our society.”

In contrast, in her response article, the author, Ms. Arguedas, is clearly more comfortable with expressing her full range when the situation calls for it. And it isn’t necessarily that one woman is wrong and the other is right: Both may simply have a good understanding of what works for them. As Ms. Arguedas concludes, “The most important thing is that an attorney maximize her power and authority in the ways that are most natural and authentic to her.” On a similar note, the ABA Journal article by Debra Cassens Weiss quotes Chicago attorney and managing partner, Patricia Brown Holmes, noting that this authenticity is the key: “The lawyer who screams or is angry at trial but is normally not that way is not often well-received. But the lawyer who shows the jury their true self — whether that is passionate, angry, sincere or otherwise — will be better received.”

An ease in using the full communication spectrum when it suits you translates into greater confidence, perhaps explaining why anger seems to work for Arguedas, but apparently not for Bazelon.

So the final implication is this: Find your own level of comfort. Don’t ignore social expectations, but don’t be fenced in by them, either. What matters most, no matter the gender, is to zealously fight for your client using all the tools that will work for you.

_______

Other Posts on Gender:

- Expect Less Gender Bias from Professional Fact Finders

- Expect Less Gender Bias from Professional Fact Finders

- Note the (Small) Difference a Female Jury Can Make

______

Salerno, J. M., Phalen, H. J., Reyes, R. N., & Schweitzer, N. J. (2018). Closing with emotion: The differential impact of male versus female attorneys expressing anger in court. Law and human behavior. 42:4, 385-401.