By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

Matthew Salzwedel in Lawyerist recently wrote about ethos, pathos, and logos in legal writing. In case you’re trying to remember that early college course in philosophy or public speaking, let me remind you of Aristotle’s famous trilogy: Ethos relates to your credibility, pathos lies in your ability to appeal to emotions, and logos is contained in your logical arguments. Salzwedel’s point is to emphasize that “ethos and pathos are logical fallacies” because they are irrelevant to legal reasoning, and that “Aristotle will smile” on those advocates who are able to forswear them in their own advocacy and rebut the two when employed by others.

The post includes much good advice on keeping one’s argument rationally focused and free of distraction. But in encouraging advocates to rely only on logos, the Lawyerist piece performs a serious misreading of Aristotle and applies a very narrow interpretation of both ethos and pathos. Viewed in context, ethos, pathos, and logos are three pillars to the same building. While legal argument appropriately prefers arguments grounded in logic, the practical need to convey a complete message means that there is a perfectly appropriate role for ethos and pathos as well. This post picks up where Salzwedel’s post left off and discusses the meaning and importance of both ethos and pathos.

Aristotle on Complete Argument

The question of what we really mean, or ought to mean, when we talk about ethos, pathos, and logos is not just an academic issue, but a practical one that extends not only to persuading juries, but to all aspects of legal argument. Contrary to what the piece in Lawyerist suggests, Aristotle didn’t equate argument with logic, and specifically didn’t consider ethos and pathos to be fallacies. Instead, he elevated the two, along with logos, into three pillars of “artistic proof,” meaning the kinds of appeals that depend not just on the strength of external evidence, but on the “art” of the advocate as well.

All three — ethos, pathos, and logos — can be engaged in ways that are appropriate and ways that are fallacious. Logos is naturally the star in the legal setting, particularly when overseen by a judge looking for rationality rather than rhetorical tactics. But even legal argument benefits from all three pillars of artistic proof, including ethos and pathos.

Ethos Can Be Ethical

Ethos doesn’t just refer to one’s perceived credibility and reputation, but also extends to the more general sense of character that is the root of the word “ethics.” Salzwedel gives the examples of a retired judge joining a private firm and having an edge when arguing before former colleagues and of former Solicitor Generals like Ted Olson and Paul Clement, having enhanced status when they come before the court they served prior to private practice. In these cases, of course, that relational advantage doesn’t make the argument itself a whit more logical than it would otherwise be. However, it does convey to the judges, “this person knows the practice and knows what they’re doing,” and that can be seen as an earned benefit of the doubt that at least ensures that they’ll receive an open-minded hearing from the judges.

But there are other ways we should think about ethos playing a role in the substantive merit of your argument. For example, the following are also implied messages that are part of your ethos:

- I am going to advocate honestly.

- I am not going to waste your time.

- I am going to focus on the essentials of the argument, not on extraneous issues.

- I am ready to discuss all relevant case law, including that which weakens my case.

- I’m going to prioritize your questions over my own planned argument.

All of these convey both credibility and respect for the forum. Part of what you are conveying is not only a sense of who you are, but also your sense of who the decision maker is, a “second persona.” You establish credibility by showing that you consider your audience to be fair, focused, and reasonable. Aristotle noted that one gains ethos by studying those who already have it, and that is where a focus on the reputation of advocates like Paul Clement can be handy. Generally, advocates have a strong reputation because they are very, very good.

Pathos Can Be Other Than Pathetic

Of course, the word “pathetic” comes from the root “pathos,” but it doesn’t mean bad or embarrassing, it means something that is capable of invoking emotion. In the Lawyerist piece, Salzwedel seems to be relying on the more colloquial sense of pathos in urging that lawyers should, “leave the politicians to peddle in appeals to emotions, feelings, sympathies, and traditions.” Importantly, pathos doesn’t just mean an appeal to sympathy or to the kinds of emotions that would be accompanied by a sad violin. Instead it embraces all of the motivating factors that drive human reasoning: what is at stake, what is my interest, and what consequences follow.

Salzwedel provides good examples of the vagueness of some legal terms (he uses “international justice” and “social justice”), potentially gaining more from emotional resonance than from defined meaning. But even as some emotions can have a dead end, the motivation remains part of the argument. Even at the level of the U.S. Supreme Court, the arguments are better and more appropriately targeted when they account for a judge’s motivating principle. Many observers, for example, have noted that the oft-swing voter Anthony Kennedy seems to make and interpret arguments based on a central organizing principle of liberty. Focusing on the judge’s motivation as the north star of your argument can help build an emotional affinity. Of course, your arguments in support of liberty or some other master principle are still logical arguments, but through selection and emphasis, you are also building a more emotional bridge to your case.

Based on popular images of lawyering, it is only natural that when we think of “pathos,” we think of someone claiming to be “the little guy,” and expressly asking for pity for their client’s sake. In most cases, that route is more likely to weaken your case than to strengthen it. You sacrifice ethos in sending the message that you’re willing to make your case in a way that is sentimental and mawkish. But emotion still has a role, and it is a critical one. It starts with the question, what motivates your decision maker to listen to your argument and care about the result?

And It Isn’t Necessarily Logical to Rely Just on Logos

What the Lawyerist post is showing through examples is that ethos and pathos fail when they place faith in appeals that are designed to supplant the logic of the argument. Perhaps the broader lesson is that persuasion is weakened when any one of the trio of ethos, pathos, and logos is allowed to stand in for the other two. Ethos in lieu of a logical argument, or pathos placed ahead of logical argument can spell doom for a legal advocate.

But the same can be true of logos as well. Focusing on logic only, and forswearing an interest in both credibility and motivation can be as dangerous and ineffective as any of the other fallacies mentioned in the post. And we sometimes see that: An advocate becomes so convinced that the logic of his argument is unassailable that he gives no thought to the likelihood that a particular judge will reject it anyway. Or an attorney has so much pride in the formal validity of her argument that she forgets to present it in a way that adopts to the decision maker and invites agreement.

A more complete view of Aristotle and a more practical position for legal advocates suggests that we should love all three: ethos, pathos, and logos. Each has their own role, and each has their own potential abuse as well. Aristotle was a man of balance and the Golden Mean after all. That suggests it helps to treat the artistic proofs as a three-legged stool: Don’t ignore any of the legs, but don’t lean too far in any one direction.

______

Other Posts on Legal Rhetoric:

- Know Your ‘God Terms’ and Your ‘Devil Terms’

- Avoid Condescension and Other Sins of Legal Argument: Know Your ‘Second Persona’

- Aim Your Damages, And Your Case, at “The Golden Mean”

______

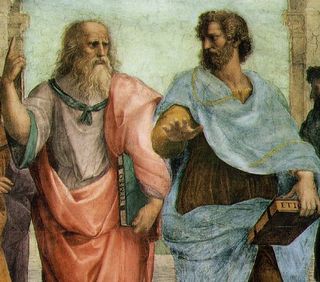

Photo Credit: Brian Sawyer, Flickr Creative Commons (Detail of “The School of Athens” by Michaelangelo in the Vatican Musem)