By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

So I almost called this post “Beware of Negative Messaging,” then I realized that that itself is a negative message. Focusing on what isn’t true, or focusing on what needs to be avoided is certainly part of communication, part of litigation, and judging from an uncomfortable number of my titles, part of this blog. But a recent essay by one of my favorite communication scholars (George Lakoff), on one of my favorite topics (political communication), made me think about the number of times in litigation where our messages may be unintentionally giving power to precisely the arguments that we want our decision makers to avoid instead of focusing on our own positive message.

Now when I say “positive message,” I want to be clear that I don’t mean that in the Pollyannish sense of emphasizing the good in everything, and rainbows and puppies and all. No, by “positive” I mean focusing more on what is true, less on what isn’t true. I mean focusing more on where we did fulfill our responsibilities, less on where our opponent is wrong in saying we didn’t fulfill our responsibilities. I mean focusing more on what we are proving, less on what we are denying. Litigation can be dark and dirty business, so we certainly can’t avoid the negative, and we generally don’t want to. But when it comes to our theme, our central message, and the choice of where we spend the majority of our time, the positive case should win out over the negative.

Lakoff on Santorum

The inspiration for this post came from an essay carried in the Huffington Post this week written by George Lakoff. As the author of Metaphors We Live By, The Political Mind, and the more recent guide to progressive politics Don’t Think of an Elephant, Dr. Lakoff is someone who is consistently illustrating the ways that linguistics and cognitive science can play a practical role in our affairs. In this essay, Lakoff takes aim at GOP contender Rick Santorum. As I’ve discussed in previous posts, Santorum has reignited debates on issues once thought to be settled (like the morality of contraception, for example). Lakoff calls this “The Santorum Strategy,” which he says is about “pounding the most radical conservative ideas into the public mind by constant repetition.” The dynamic is that even when decisively refuted, these ideas end up changing the debate and altering our frame of reference. “All thought is physical” he argues, and “brain circuitry strengthens with repeated activation…Conservative language, even when argued against, activates and strengthens conservative brain circuitry.”

Of course, he is targeting an audience of political progressives. And his advice to that audience is that if you are continuously occupied with refuting conservative beliefs like Santorum’s instead of building your own case and moral vision, then even as you win the argument, you end up strengthening a conservative frame of reference and increasing the space and relevance for conservative ideas. There is a lesson there that people of all political stripes can take to heart: play more offense than defense. Don’t content yourself with refutation, because even that negative attention can end up creating more space and acceptance for a bad idea.

Choosing a Positive Message

I was recently being briefed by a client on a new case. As the attorney told me about his fraud defense, he focused on the limits of his company’s responsibilities: “We didn’t have an agreement with them…We didn’t make any promises to them…We didn’t have a fiduciary duty to them… We didn’t have any contract with them.” Okay, I say, so that characterizes what we didn’t have and what we didn’t do. What is the flip side of that — what was our relationship, what were our responsibilities, and what did we do? “Oh, that is easier: They asked us for advice and we gave them advice.” So that creates a theme that emphasizes both the positive and the negative: It was a question, not a contract.

There are some good reasons to include a focus on both the positive and negative, like I titled a previous post “In Eggs and Arguments, Keep the Sunny Side Up But Cook Both Sides.” But Lakoff’s reminder is that majority of our time should be spent on the positive side of the argument, or we are inadvertently giving force and power to the negative side.

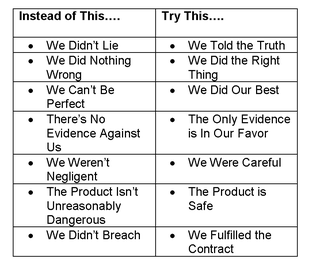

How you strike the balance will depend on the specifics of your case, but here is a quick table to illustrate what I mean by positive framing:

Those are simplifications of course, but we find that too often litigation themes are closer to the left-hand column. If you are focused on refutation, as litigators often are, that will often lead you in the direction of the negative message. However, for nearly every negative message, there is a positive way of framing it. The difference between the two might seem like an insubstantial bit of window dressing, but from a cognitive perspective the difference is huge. The positive is assertive, the negative is defensive. The positive is concrete, the negative is abstract. But more than that, the positive directs attention to your argument while the negative directs attention to theirs.

______

Other Posts on Messaging:

- Take a Lesson from Political Campaigns: Going Negative Works (Partially)

- With Eggs and Arguments, Keep the Sunny Side Up, But Cook Both Sides

- Persuade Using Both Alpha and Omega Strategies

______

Image Credit: Bluekdesign, Flickr Creative Commons