By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

While researching for a previous post, I was reading Professor Dru Stevenson’s (2012) article in the George Mason Law Review, and I came across a jarring sentence asserting that “modern approaches to jury selection” focus on biases relating to factors “such as race and gender.” The author then followed up in a footnote: “Most indicative of this consensus is the widespread use of JuryQuest software and similar products which compute values for each prospective juror based on such factors.” Never heard of JuryQuest? If not, you are forgiven. In sixteen years of working with consultants and attorneys providing assistance on jury selection, I haven’t come across anyone using it. Nothing in either Stevenson’s article, or the article he cites in the footnote (Gadwood, 2008), supports the claim that use of JuryQuest is “widespread.” Instead, then law student now attorney James Gadwood, notes the software’s use in the Andrea Yates trial, as well as the handful of client firms – geographically distributed, but not terribly numerous – that are listed on the software maker’s website.

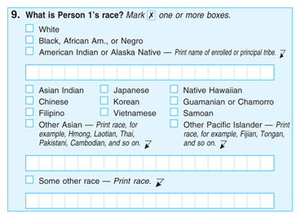

Beyond the JuryQuest software, the central mystery in both articles is the belief that demographics occupy a central place in modern jury selection. That is like claiming that the accordion occupies the central place in modern music – it is very nearly the opposite of the truth. For at least three decades, researchers have known that demographic factors like race, gender, age, and education are very weak predictors of verdicts, and those who make their living assisting in jury selection have focused instead on learning about the experiences and attitudes that bear upon the issues closest to the case. Still, the perception persists that courtrooms are teaming with consultants and attorneys who are applying the questionable science of demographic prediction, fueled by commentary like Gadwood’s and Stevenson’s, and perhaps by the continued existence of products like JuryQuest. This post aims to correct that misimpression, and to emphasize the factors that truly matter when selecting your panel.

No, Modern Jury Selection is Not Dominated by “JuryQuest” Demographics

The central point that James Gadwood makes about JuryQuest is well-founded: the computer program is a walking Batson challenge. By formally incorporating and weighting seven demographic facts about your potential jurors (race, gender, age, education, occupation, marital status, and prior jury service), the program formally relies on the very criteria that Batson, and its related cases like J.E.B. v. Alabama, mark as the sign of an impermissible strike. Gadwood does a very effective job of unpacking the standard and applying it to the use of a program like JuryQuest, and his analysis concludes by urging courts to adopt means to expose the use of “a jury selection tool which unabashedly operates, at least in part, on the basis of constitutionally impermissible characteristics, directly contravening Batson and its progeny” (p. 318-19).

But where Gadwood errs is in overstating the field’s reliance on this tool. He quotes the attorney who successfully won an insanity defense for Andrea Yates (“You can’t overemphasize the importance of the software…”), but his only support for the claim that use is “spread across the legal industry” is a reference to JuryQuest’s own client list on the company’s website. As of today, that list includes six civil firms (four in Texas, two in California), twenty-three criminal firms or lawyers, and eight public defender offices. Consultants who work more in the criminal arena (I do, but it is chiefly white collar) may see more use of a tool like this, but I would be somewhat surprised if they did. There is no discussion of the tool that I’m aware of within trial consulting circles, and I have trouble believing that experienced attorneys would set aside their own judgment and evaluation of what they learn from specific venire members and instead rely on the software’s demographic formula.

No, There is No Case for Relying on Demographics

Nor should attorneys set aside their judgment and evaluation in order to place their faith in demographics. Even if there were no Batson and no progeny, there is simply no social science case to be made for the reliability of demographics as a predictor of juror bias. On this point, the consensus of litigation consultants is clear, and the research backs it up. To choose just a couple of examples, Fulero & Penrod (1990) reviewed the approach of tying demographics to verdicts and found that demographic variables are at best only modest predictors of verdicts. More recently, Joel Lieberman (2011) notes that the asserted relationship is “still murky after 30 years.” While broadly condemning the label of “scientific jury selection,” what this research is really critiquing is a reliance on demographics, which social scientists in the business have largely given up.

A critical read of the JuryQuest website points out some of the reasons why. The company’s database uses the seven identified questions alone to rank jurors on a 100 point scale as favoring or opposing your case. This ranking, however, is not based on published research, but based on JuryQuest’s own proprietary database of the questionnaire responses of “nearly 45,000” individuals. The tool’s published success rates, much higher than average for both civil and criminal clients, are also based on the company’s own analysis. The website quotes research, but not anything that supports the predictiveness of its demographic criteria. Instead, oddly, the website emphasizes the Kalven & Zeisel 1966 finding that jury verdicts tend to be consistent with that jury’s first vote.

The unanswered question is whether jury verdicts or first votes are predictable through demographics alone. Or more pointedly, why would just seven demographic variables fare better at predicting bias than a more specific voir dire on your own case? “Since strongly felt values of individuals are reinforced in group settings (deliberations),” the website explains, “It is important to obtain systematic evidence on values by social groupings, rather than relying on attempts to infer values from questioning individuals in voir dire.” Unpack that statement and it quickly falls to nonsense because jurors tend to reinforce each other in deliberations. You should trust the fact that a juror’s demographic group (e.g., caucasian) holds a given value (e.g., a law and order mentality) more than you trust what you learn from the specific individual juror in voir dire? Why?

While there is good questioning and bad questioning, as we’ve written before, there is no reason to trust what is true in the aggregate more than you trust what is true in the individual. So one demographic group may be more likely to hold a specific value, but nearly always that difference, even when statistically significant, is likely to be relatively minor and to explain far less than the majority of variability you see in the attitude. In other words, you will find about as many individuals who conflict with the stereotype as confirm it. So even when dealing with a real demographic difference, you are better off finding out what the individual thinks. After all, it is the individual and not the demographic group who will be sitting in judgment on your case.

No, Demographics Are Not Even a Good “Starting Point”

In some of the early press that this program received, criticisms like the ones I’ve leveled are often answered the way attorney Jason Webster did in a 2006 National Law Journal article: “It’ll never replace asking the juror questions, but it will give you a good place to start.” That starting place, however, might be a Batson challenge that just requires the judge to be shown the JuryQuest website. However, even if there was no Batson, and even if I stipulated that the demographic correlations are genuine, I’d still argue that demographics don’t provide “a good place to start” for a couple of reasons.

1. Demographics create a false sense of specific knowledge. As I say, even where a correlation is real, it is likely to be minor. That means that close to half the time, what is true in the aggregate won’t be true in the individual. But when you start with a demographic conclusion, you might feel like you have knowledge about the individual’s attitudes and values that bear on your case, but in reality, you don’t.

2. Demographic reliance may crowd out better sources of information. We know that humans are prone to selective perception and tend to notice what confirms our expectations more than we notice what refutes it. In that way, a demographic expectation can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Or worse, attorneys used to thinking that demographics provide the answer may make less effective use of voir dire, or may be less aggressive in pressing for expanded voir dire.

In truth, the biggest culprit in promoting reliance on demographics is probably not software makers or consultants. It is courts that permit no substantive questionnaires, and either no or severely restricted oral voir dire — limits that induce attorneys to rely on what they can see only, and to believe that it means something. My own view is that when you don’t have good information, you are better off basing your strikes on the most traditional factors: case and party knowledge, involvement in similar cases, and the other concerns that might emerge during the judge’s questioning without quite rising to the level of a cause challenge. When all else fails, you can make some reasonable judgments based on occupation, because that at least ties in to a potential juror’s daily life experience. Occupation is one of the seven factors considered by JuryQuest, but so far at least, it is a factor free from Batson-related concerns.

Yes, Attitudes Are Still Your Best Cues to Juror Bias

The bias that jurors bring into the courtroom with them usually takes the form of attitudes. In many cases, those attitudes are fostered by important life experiences. And in some cases, those experiences can be related to demographics. But in all cases, it is the resulting attitudes that are doing the work. For that reason, the best voir dire strategy should focus on uncovering attitudes.

While some in the popular press, and even scholars have equivocated between “Scientific Jury Selection” and “Demographic Jury Selection,” there are definitely systematic and scientific ways to focus on the attitudes that matter most in jury selection, as we’ve written in the past. Granted, much of the useful advice that consultants supply during jury selection will be subjective in nature and will supplement the attorney’s own subjective interpretations. But where quantitative social science techniques apply, they should apply first and foremost to the attitudes that will drive juror decision making. One example of Scientific Jury Selection that is not based on demographics can be found in our own Anti-Corporate Bias Scale, a validated measure of the attitudes that determine initial leaning in an individual versus corporation case. It is still science, just based on a much better foundation than demographics.

Epilogue: Don’t Hate the Technology

One of my biggest irritations with a program like JuryQuest, and the attention it has received from scholars like Stevenson and Gadwood, is that it gives a bad name to technology used in jury selection. Skepticism of the ability of “a computer” to pick your jury, for example, might unfairly tarnish many of the more modern approaches to laptop or iPad aided jury selection. To be clear, the tools that I’ve used and reviewed — Jury Box, iJuror, and Jury Duty — do not make a similar demographic calculation to tell you who is at risk. Instead, these tools serve as sophisticated versions of the old Post-it note grid in order to systematize the choice for the attorney. The best among them allow the user to apply a weight to the information learned, and to calculate a resulting score for the prospective juror, but importantly, that score is based on the users’ own sense of what matters to their own case.

______

Other Posts on Jury Selection:

- Don’t Build Your Jury Out of Leftovers

- Voir Dire at the Intersection of Your Case and Their Life: For Energy Litigation, that Means Gas Prices

- Tap Into Computer-Aided Jury Selection: A Video Review of Jury Box Software

______

Gadwood, James R. (2008). The Framework Comes Crumbling Down: Juryquest in a Batson World Boston University Law Review, 88, 291-319

Gadwood, James R. (2008). The Framework Comes Crumbling Down: Juryquest in a Batson World Boston University Law Review, 88, 291-319

Dru Stevenson (2012). The Function of Uncertainty Within Jury Systems George Mason Law Review, 19 (2), 513-548

Image Source: spotreporting, Flickr Creative Commons, 2010 U.S. Census Form