By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm

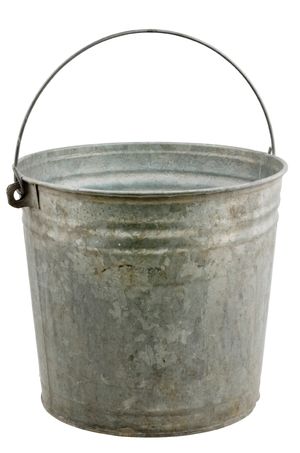

The law treats factual evidence as a repository possessed by the witness and elicited through testimony. Like a bucket, filled, in the case of your witnesses at least, with the sweet clear water of truth, you just dip in a ladle and out comes the descriptions, the observations, the facts. We acknowledge that the bucket isn’t perfect: It holds only so much, and is prone to leaking. But we still treat testimony as the act of information retrieval, not fully accounting for the possibility that the bucket is at all times fundamentally transforming its contents. However, to a degree even greater than researchers expected, a new study (Bridge & Paller, 2012), confirms that transformation during recall is the norm, not the exception. That is, we rewrite every time we remember. In recalling, we reconstruct by mixing the original memories with our recollection of the previous times we’ve thought about and shared the same information.

The law treats factual evidence as a repository possessed by the witness and elicited through testimony. Like a bucket, filled, in the case of your witnesses at least, with the sweet clear water of truth, you just dip in a ladle and out comes the descriptions, the observations, the facts. We acknowledge that the bucket isn’t perfect: It holds only so much, and is prone to leaking. But we still treat testimony as the act of information retrieval, not fully accounting for the possibility that the bucket is at all times fundamentally transforming its contents. However, to a degree even greater than researchers expected, a new study (Bridge & Paller, 2012), confirms that transformation during recall is the norm, not the exception. That is, we rewrite every time we remember. In recalling, we reconstruct by mixing the original memories with our recollection of the previous times we’ve thought about and shared the same information.

So memory is creative rather than descriptive, and dynamic rather than static. That goes to the heart of a trial court’s reliance on testimony. Eyewitnesses in criminal cases get the most attention (which makes sense based on what is at stake), but the problem bears on civil trials as well, because it influences how we should treat all testimony that depends on recollection…which is to say, all fact testimony. Even the civil litigation witness may be creating as much as he is remembering, and it isn’t a conscious attempt to mislead. This post looks at the new study and unpacks a few ways that trial lawyers can adapt to the realities of reconstructive memory.

The Study

The researchers (Bridge & Paller, 2012), a psychology professor and a postdoctoral fellow in medicine at Northwestern University, conducted an experiment asking people to recall the location of objects on a grid, then complete recall tests on a subset of those objects on a second day, and then again on a third day. What the study showed with each person tested is that memories don’t simply deteriorate in a random fashion. Instead, prior recollection changed the memories and participants were more influenced by their errors in recollection on day two than they were by the correct information viewed on day one. In addition, recall in the final session was actually better when an object was tested on day one, but not on day two. As lead author Donna Bridge explained in a Northwestern news release, “Retrieving the memory didn’t simply reinforce the original association. Rather, it altered memory storage to reinforce the location that was recalled at session two.” In other words, we don’t remember without revising.

“A memory is not simply an image produced by time traveling back to the original event — it can be an image that is somewhat distorted because of the prior times you remembered it,” according to Bridge, “your memory of an event can grow less precise even to the point of being totally false with each retrieval.” While there is a long tradition of research showing the failures of precise recall, this study is the first to show that recall is often most influenced not by the original event, but by what you remembered the last time you recalled that event. As Bridge explains, “If you remember something in the context of a new environment and time, or if you are even in a different mood, your memories might integrate the new information.” In other words, it is difficiult to remember without revising.

The researchers also measured participants’ neural signals during the recall tasks and found that signals measured on the final day were strongest when objects were placed closest to the location remembered on day two. “The strong signal,” Bridge explained, “seems to indicate that a new memory was being laid down, and the new memory caused a bias to make the same mistake again.”

So understanding that memories are creative by nature, how should lawyers adapt in court?

When You’re Attacking Recall

When you are looking to weaken the effect of recall testimony from the other side, here are a few implications.

Don’t Trust a Memory Just Because It is Honest and Unbiased

The traditional tools for undermining a witness are to focus on bias or uncertainty. But when an otherwise credible witness says, “I’m sure,” what then? The lesson of this and other studies is that dishonesty doesn’t have to be an intentional act. Instead, that certainty can be an effect of the psychology of repeated tellings – something the trial preparation process encourages.

Make Them Remember More than Once or Twice

Obviously you can’t waste time in a deposition or, especially, in front of a jury. At the same time, there is something to that old police interrogation trick of asking for the story multiple times – you know, when the detective gets another cup of coffee and says “…okay, lets take it from the top.” Repetition shows inconsistencies, and inconsistencies introduce doubt.

Access All the Versions

It makes sense to ask, “How many times have you shared this story…to whom…in what contexts?” Asking these questions at the deposition stage can point you to other witnesses and, hopefully, get you closer to the first version of the story. It is that first version version that jurors are likely to – accurately – see as the most credible and least influenced by subsequent recollection.

When You’re Buttressing Recall

Of course, even with its flaws, a reliance on recall in fact testimony is a necessity. When dealing with your own witnesses, here are a few good practices for protecting and defending the veracity of witness memories.

Lock Down a Version Early

Knowing that the meetings with attorneys and the witness preparation sessions may exert as strong an influence on memory as the original events themselves, it is critical to establish and record an accurate version as early as possible. Draw a clear distinction between what the witness remembers and doesn’t remember, and then ensure that the remembered part stays as consistent as possible.

Usually, Keep Witnesses Out of Broader Strategy Discussions

While it is important for witnesses to have a basic sense of what you and the other side are trying to show, it can often be key to limit the strategic thinking of your witness. Taking part in long strategy discussions with the trial team can’t help but influence the witness’s recollection, frequently in ways that aren’t helpful or consistent.

Talk About Reference Points

Especially in the case of conflicting testimony, jurors often wonder, “How does the witness know that they’re remembering accurately?” It is a good question, and it is not enough to just talk about how “certain” the witness is. Instead, a reference point can help. For example, “I do remember inspecting the car before I left the rental lot, because I noticed that the ashtray was full, which was odd.” Adding that irrelevant detail makes the story more credible than the simple, “Yes, I’m sure I inspected the car.”

Of course, none of these techniques are a foolproof way to avoid the alterations of memory documented in the Bridge and Paller study. The most important lesson is to remember that witness testimony is only part of the picture, and witnesses aren’t just buckets of facts. To update the analogy, perhaps memory is more like what you might see in your firm’s computer file management system. Looking at the directory, you are tempted to see a document as a single thing. But open up the “history” tab on that document and you’ll see when it was created, accessed, revised, saved, emailed, etc. In that context, the current version is just the current version. Like a witness.

______

Other Posts on Memory:

- With Computers and Witnesses, Expect Memory Errors

- Know the Limits of Limiting Instructions (But Don’t Necessarily Discard the Instruction to Disregard)

- Remember Herman Cain’s “9-9-9” Plan, and Don’t Forget the Power of a Good Mnemonic

- Remember, Jurors Are Always Forgetting

______

Bridge, D. J. & Paller, K. A. (2012). Neural Correlates of Reactivation and Retrieval-Induced Distortion. Journal of Neuroscience 32 (35). 12144-12151. URL: http://www.jneurosci.org/content/32/35/12144.short

Photo Credit: iStockphoto, used under license