by: Dr. Ken Broda Bahm

If you have had a trial docketed within the last year or in the coming year, then chances are that you have wondered whether current economic hard times have encouraged in juries either a greater impulse to distribute money from corporations to individual plaintiffs, or conversely, a tight-fistedness that has held down damage awards. While jury wisdom or social psychology arguments could be marshaled in support of either supposition, on the question of whether hard-times have turned jurors into benefactors or misers, the data so far at least seems to answer “no,” and “no.” Even in the face of a current economic recession in which about eight out of ten Americans report to have been personally affected, juries continue to award or resist damages based on long-established tendencies. You wouldn’t know that, however, from the spate of recent commentary on the recession’s expected effects in the courtroom. In a recent piece in The Jury Expert, University of Colorado Professor Edie Greene notes several examples of speculation on the effects of a recession on jurors moving in either direction. Commentators reason that the recession could be good for plaintiffs (because of the anger directed against corporate America) or bad for plaintiffs (because of the widespread nature of the suffering and the feeling that plaintiffs are no worse off than anyone else). A recent example of this line of commentary was published in the Wisconsin Law Review this week, but as Dr. Greene notes, the real answer will depend on what the data tell us.

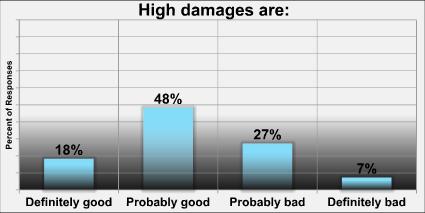

Persuasion Strategies researched the question through a national randomized telephone survey of 500 jury-eligible Americans conducted in March of 2009, just as the AIG “bonus-gate” controversy was reaching its zenith. The results of that survey, discussed in a recent Special Report in the September issue of InsideCounsel, show no sea change in attitudes toward defendant corporations or greater willingness to award damages. Respondents were no more likely than in past years to agree that if a suit has been filed, then it probably has merit. When asked to consider a hypothetical example of a corporation employing a large number of individuals that has been found in court to have caused damage due to greed or irresponsibility, respondents were more likely to consider high damages to be “good” in that case (after all, they’ve been asked to assume guilt), but there is no clear preference for the extremes: only 18% considered high damages to be “definitely good,” and just 7% considered high damages to be “definitely bad.”

Dr. Greene’s conclusion was that “jurors’ past priorities will hold in the vast majority of future trials” and that “the main action still happens on the witness stand; the recession is merely a backdrop.” That conclusion appears to be bourn out both by national survey data as well as by recent experience in the courtroom. Plaintiffs appear to prevail or fail most often for all of the old reasons: The Defendants take responsibility, or don’t take responsibility for their actions, and the Plaintiffs survived or don’t survive the scrutiny that all plaintiffs face.