By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

Here is one belief I’m pretty sure about: Most of us tend to be pretty sure about our beliefs. As the waning campaign season has continued to demonstrate, we tend to select a chosen belief and stick to it rigorously, even in the face of contrary information. In our personal campaign to understand the world, we are not dictated by the fact checkers. Substantial portions of the American public believe that Barack Obama was not born in the United States and is a Muslim, that childhood vaccines cause autism, that there is no consensus on human-caused global warming, or that the Bush tax cuts increased revenue for the government. All of those beliefs can be refuted with hard evidence, but they’re sticky. For many, the refutation just hardens the resolve to stay with current beliefs.

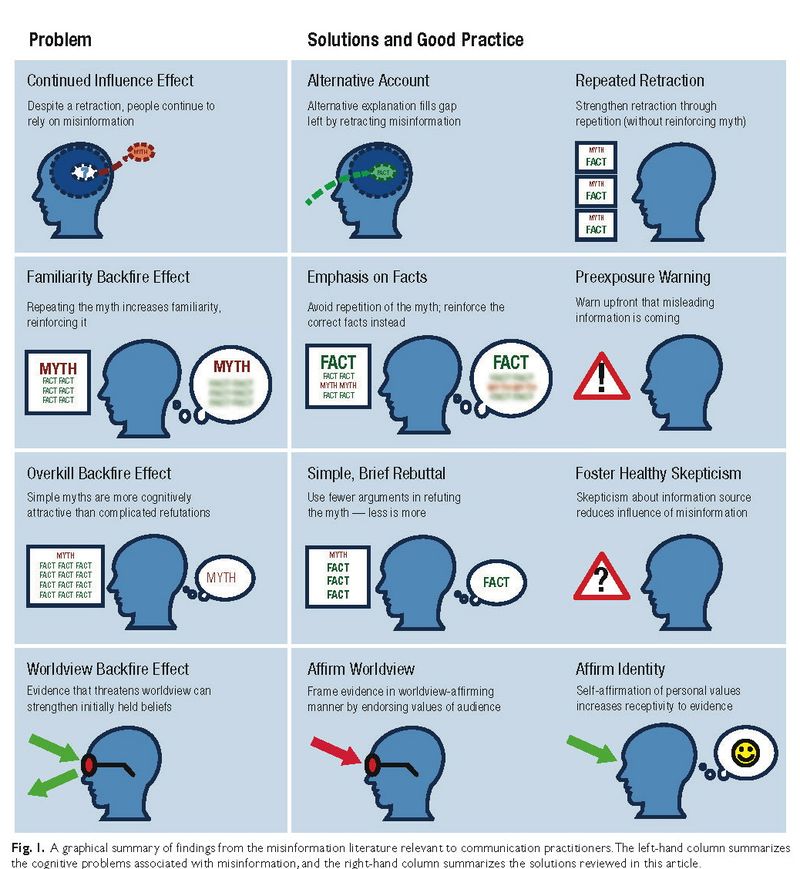

In litigation, jurors may find many forms of misinformation sticky as well. They may believe that if a lawsuit makes it to trial, or even if it is simply filed, then there must be something to it. They may believe that a corporation will always lie, or always put profits ahead of people. They may feel that juries are cash machines motivated primarily by sympathy. They may believe that most or all lawsuits are frivolous, buttressed by misinformation on the McDonald’s Hot Coffee case. They may believe that if a product has met relevant regulations, then the product maker and seller is immune to suit. Countering these and other forms of misinformation can be an important part of legal persuasion. A recent research review (Lewandowsky et al., 2012) takes a broad look at the accidental and purposeful contributors to misinformation — traditional media, interest groups, social media and even, gulp, bloggers. The article (which is available in full and is free) provides a very comprehensive review, to the point that reading the entire piece is a veritable graduate course in the persistence of B.S. But unlike many research articles, this one is particularly helpful in providing specific recommendations for debunking misinformation. In this post, I take a look at how these recommendations can be concretely applied to cut through sticky misinformation in a trial context.

These solutions take on more practical meaning when applied to an example. Taking one that is handy, the November issue of the ABA Journal out today includes a cover story on the role of neuroscience in trial, pointing out that our evolving understanding of the role of brain physiology is running up against our traditional and practical understanding of legal responsibility. One example of misinformation that applies in criminal cases, as well as some civil cases, is the popular and sticky belief that personal responsibility, and a knowledge of the difference between right and wrong, can trump even more profound and demonstrable forms of mental illness.

Drawing from that example, let’s take a look at how the researchers’ four forms of misinformation and related solutions would apply.

1. The Continued Influence Effect

Even after erroneous information is retracted, studies show that the incorrect information will have a persistent influence as people continue to rely on it. Even in the face of expert medical testimony that an individual lacked intention, for example, individuals will continue to treat the individual as a moral agent. The solution, according to the researchers, is to provide an alternate account that is as simple as the misinformation. That is, instead of just providing refutation (“That isn’t true”), fill in the gap (“Here is what is true”). In the case of brain injury and moral responsibility, that can be a challenge because nothing is simpler than the idea that we are all responsible for our actions no matter what. The alternate account in this case needs to be an argument with comparable simplicity. One option might be found in the idea of a “missing regulator” discussed in the ABA Journal article. Everyone has impulses, like the gas pedal on a car, but just about everyone also has brakes. In the case of some brain-injured defendants, however, they may look and act normal in many contexts, but in other situations they simply have no brakes.

2. The Familiarity Backfire Effect

When a myth is repeatedly rebutted, even the rebuttal can end up reinforcing the familiarity of the myth and making it more likely to be remembered and repeated. Advocates might think they’re pounding the false belief down and making it unsustainable, but they’re actually just raising its profile. The solution, according to the research team, is to focus on what is true rather than what is not. In the case of showing a lack of legal responsibility, for example, it won’t help to keep emphasizing “my client did not know right from wrong.” Instead, the message should be, “my client only had a basic understanding that there are police and there are laws…but he lacked the empathy to understand why.” The authors also note that one other strategy to guard against the familiarity of misinformation is to warn in advance. For example, counsel could say in jury selection, “you will hear the prosecution emphasize again and again that my client understood the law, but that is not the whole story.”

3. The Overkill Backfire Effect

Another way attempts to correct misinformation can backfire is through overkill. If refutations are more elaborate or more complicated than the myth itself, then the myth is the more attractive belief. In the case of assigning legal responsibility to brain-injured defendants, it is certainly attractive to believe that everyone carries responsibility for their actions, because the alternative is to believe that blame lies nowhere. In this case, the researcher’s advice is to use fewer arguments in rebutting a myth — the one very good argument being often better than the three somewhat good arguments. In addition, they argue that a good antidote to misinformation is for the audience to consciously adopt a skeptical frame of mind. In this regard, the context of a jury helps because jurors know that both sides have a strong motivation to persuade them and their job is to remain skeptical and test the evidence. A brain-injury defense could assist jurors in embracing that frame by reminding them that their role is to test, and they should test the prosecution’s assumption of personal responsibility as much as they test the defendant’s information on brain injury.

4. Worldview Backfire Effect

The final explanation the researchers offer for the persistence of false beliefs lies in the critical area of worldview. We want to believe in a just world, a moral universe where bad things don’t simply happen, but are instead the result of poor choices. In this case, jurors might simply be threatened by the idea that a brain-damaged individual cannot control and cannot be responsible for her actions. It is more comfortable to believe, even without evidence, that “deep down,” the accused knew the actions were wrong and could have stopped them. In this case, the evidence points toward an adaptive strategy. You’ll never succeed in convincing someone that their worldview is wrong (e.g., “sorry, but we really do live in a random universe…”), but you can sometimes find a way of framing your argument in a way that is consonant with that worldview. For example, counsel in a brain injury defense might say something like this: “In this case, the attorneys for both sides, the judge, the court personnel, and each of you on the jury all have personal responsibility. That responsibility is to make choices rationally, carefully, and thoroughly, based on what the evidence shows, not based on what we expect, what we assume, or what we want to be true. It is your own personal responsibility that requires you to take a hard and unbiased look at the medical evidence you’ve heard.”

Of course, none of these techniques is fool proof. Even after a tailored strategy to address misinformation, some jurors will stick with misinformation anyway because it is familiar and comfortable. That is why you have jury selection, and why you should spend that time discovering what jurors believe they already know within the broad frame of your case. It will always be easier to avoid misinformation than to correct it.

______

Other Posts on Attitude Change:

- Adapt Your Scientific Testimony to Jurors’ Skeptical Ears

- Convert Your Conspiracy Theorists: Research Shows it Can Be Done

- Beware of the Jury’s “Filter Bubble”

______

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U., Seifert, C., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13 (3), 106-131 DOI: 10.1177/1529100612451018

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U., Seifert, C., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13 (3), 106-131 DOI: 10.1177/1529100612451018

Photo Credit: Ivy Dawned, Flickr Creative Commons