By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

It is well-known at this point that civil trials are giving way to settlements. One of the factors that make settlement the more attractive alternative is that settlement is an uncertainty-reduction strategy: The known amount of cash in or out of pocket reduces the risk of the unknown for both plaintiffs and defendants, making the settlement a route for clients, lawyers, and insurers that is more comfortable than facing the jury. And the aspect of a jury that is most uncertain and most uncomfortable is generally the damages. The caricature of juries from a client’s-eye view is that they’re unmoored on the amounts, and prone to pick awards driven by whim or idiosyncrasy, particularly in the noneconomic categories. If the jury is viewed as a black box, then the darkest part of that box is definitely damages. Beyond the anecdotes, however, the research looking at the ways jurors actually arrive at damage numbers reveals a more nuanced picture.

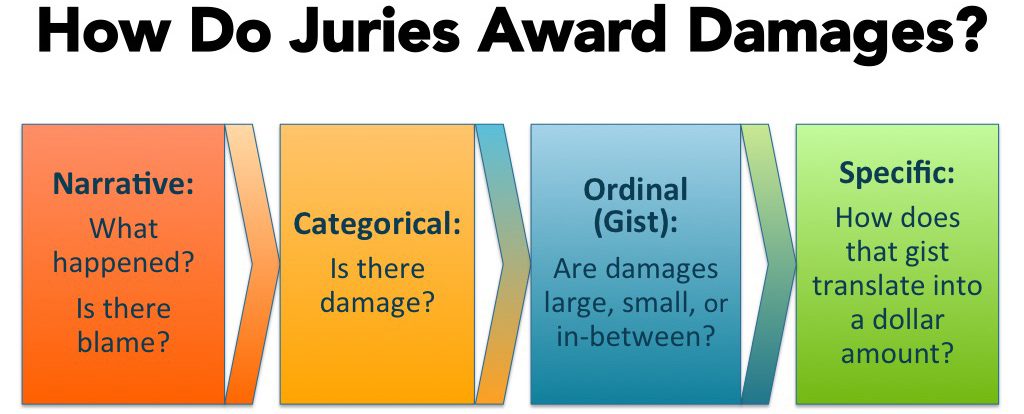

In recent years, social science has demonstrated that, even when picking numbers in open-ended categories like “pain and suffering,” there is more method than madness from the jurors. The working model, often imprecisely called the “gist” approach, posits that jurors move through phases in arriving at a categorical decision on whether damages are warranted or not, then an ordinal decision on whether they should be “high,” “low,” or “medium,” before finally mapping that decision onto a numerical amount. A recent study (Hans, Reyna, & Helm, 2018) adds further confirmation and understanding of that model. Researchers from Cornell and Exeter tested the model along with the influence of anchors and factors that led to difficulty. Specifically, they looked at the effectiveness of making numbers meaningful by, for example, relating a noneconomic figure to an economic one, like one year’s income. “Providing meaningful anchor numbers,” they found, “helps mock jurors choose damage amounts that correspond to their underlying sense — the gist — of an individual’s pain and suffering.” However, it isn’t an easy path, and those who have the greatest difficulty with it aren’t those we would expect. In this post, I’ll share two findings, along with implications for litigators either arguing damages or considering the parameters of potential damages when deciding on settlement.

The bottom line of the research is that jurors approach damage numbers in two broad ways: in stages and with difficulty.

In Stages

Jurors don’t simply arrive at a gestalt view of the right damages number from a blank slate. Instead, they move through a process, making a translation from a qualitative to a quantitative judgement. In a previous post, I shared a simple graphic we developed to illustrate the gist of the “gist model:”

While any given juror won’t necessarily be mechanical about approaching each step in sequence, jurors will reliably address each of these phases in some fashion. For that reason, it makes sense to account for this model when addressing damages. For example, in approaching the ordinal decision of whether damages are high, low, or medium (an area where researchers find greater consensus among jurors), it helps to think about the messages you are sending on that question: What is it about the situation in this case that tells them that damages ought to be greater than, lesser than, or about the same as normal?

And With Difficulty

But even with attention to “gist” and with meaningful anchor numbers given, the task or arriving at a number is still difficult. To assess this difficulty, the researchers looked at a number of factors: need for cognition, objective and subjective numeracy (the mathematical version of “literacy”), as well as differences in cognitive reflection style.

Interestingly, what did not seem to matter in determining the results was overall cognitive ability. They explain, “given the same case facts, more cognitively able individuals were not more likely to give smaller, larger, or more variable pain and suffering awards.” So this suggests that a preference for smarter jurors would not reliably help either side.

However, cognitive ability did predict the perceived difficulty of the task, and in a direction that might be opposite of what you might presume. Individuals with greater numerical skills found it more difficult to arrive at a damages number. This may be simply because the less able just rely on a heuristic shortcut (a “nice round number”), while the more able see no option other than to work through it. The authors explain, “More numerate people may have recognized the difficulty of making pain and suffering award judgments to a greater extent than less numerate people.”

So remember when arguing damages, you aren’t just preaching for or against a particular number. Instead, you are teaching a process for jurors to use to arrive at their own number. With the process you teach, the number ought to trend in the direction you favor, but ultimately it will still be the jurors’ own number, not yours. The more they understand how to get there on their own, the better they’ll feel. And the more they are able to comfortably apply the process you recommend, the more predictable the ultimate number will be.

______

Other Posts on Damages:

- Make Your Damages Numbers Meaningful

- When Arguing Damages, “Drop Anchor” Even in Murky Waters

- Get the Gist of How Jurors Decide Damage Numbers

- A Mixture of Justice and Revenge: Target Juror Psychology in Awarding Damages

______

Hans, V. P., Helm, R., & Reyna, V. F. (2018). From Meaning to Money: Translating Injury into Dollars.Law and Human Behavior 42:2, 95-109.