By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

It’s the political season, and many of us are closely watching the public opinion polls. It is interesting to see that sometimes big differences between polls are caused by small differences in wording. Do Americans “prefer,” “support,” “favor,” or “intend to vote for” a given candidate? Different words make for a different result. Question wording matters in jury analysis and selection as well. In community attitude surveys, change of venue motions, supplemental juror questionnaires, and oral voir dire, the specific words we choose for the question can strongly influence the result. One area where this problem can be acute is in rehabilitation, or the attempts by court or counsel to determine whether a potential juror can still be fair despite having expressed a bias. Psychology professor Mykol Hamilton of Centre College even coined the term “prehabilitation” to describe the common process of subtly or expressly talking panelists out of biases prematurely, before those biases have even been expressed. In a current article in The Jury Expert, the same lead author along with Kate Zephyrhawke of Hillsborough Community College carry their research one step further, and turn in one of the first efforts to quantify the differences in results stemming from various phrasings of two commonly-asked questions in voir dire.

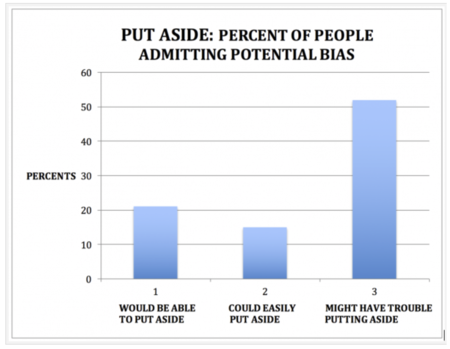

The article (Hamilton & Zephyrhawke, 2015) looked at the question of whether potential jurors could presume the defendant is innocent until proven guilty in a criminal context. In addition, they looked at the common question of whether the potential jurors could “set aside” their prior knowledge and attitudes in hearing the case. They surveyed 401 jury-eligible adults on their knowledge and views relating to a highly publicized Kentucky murder case. The researchers converted the questions to scale-questions (e.g., “strongly agree,” “agree,” etcetera) rather than yes/no questions (in the view that the gradations give respondents greater comfort in admitting to some bias without agreeing to the extreme end of bias). But the main manipulation was to compare the effectiveness of questions focused on ability (e.g., “Would you be able to…?”) with questions focused on ease or difficulty (e.g., “How easy or how hard would it be to…?”). The thinking is that the questions focused on ability would be seen as a question about the potential juror’s competence, while the wording focused on ease or difficulty would instead normalize the authors possibility of being challenged in being fair. Based on their results, that seems to be the case. “Had we only asked the traditional, leading, prehabilitatively worded ‘Assume’ and ‘Put Aside’ questions in the Kentucky [change of venue] survey,” the authors reported, “we would have concluded that only about one in five doubted their ability to put aside opinions when in fact over half of them did.”

In a previous post focused on Hamilton’s work (“Don’t Prehabilitate”), I gave my own outline of what I call the “Juror Candor Toolkit,” a set of principles for phrasing questions focused on varying the context, control, and complexity of the questions in order to vary the response. That is still an approach I stick with. But the current study adds empirical data on specific wording that supplements our knowledge of what words to use and to avoid when rehabilitating jurors for cause.

To me at least, it depends on whether you are trying to keep the potential juror or lose the potential juror.

When You’re Trying to Keep the Panelist (or Force a Strike by the Other Side), Ask About Ability

The phrasing that is less likely to lead to an admission of bias, and more likely to lead to a “Sure I can be fair,” is the phrasing that asks whether the individual would be able to put aside their prior knowledge and attitudes.

The advice of Hamilton and Zephyrhawke is that ‘ability’ questions should simply be avoided. “In all three situations, COV surveys, jury surveys, and voir dire,” they write, “we should avoid words like ‘able,’ and phrases like ‘can you?'” But in a response to the article also published in The Jury Expert, Litigation Insights consultant Christina Marinakis makes an important point: If a potential juror is good for you but admits to a potential bias against the other side, then as a zealous advocate, you would have every reason to ask the question in such a way that makes it easier for the panelist to say they could be fair. It is not so much a matter of promoting bias as it is a desire to not do the other side’s work for them.

When You’re Trying to Get the Panelist Excused, Ask About Difficulty

When you want the rehabilitation to be unsuccessful, the potential juror needs to stick with their bias. And it is easier to agree if the question is just asking you to admit to some difficulty. The ‘difficulty’ phrasing is the clear winner in the study. “The differences between the two percentages,” they write, “suggests that when the put aside question is posed in the traditional [ability-focused] way in the courtroom, it is likely that about one-third (31 percent) of prospective jurors will misrepresent themselves, not admitting they would struggle to put aside prior opinions when in fact they would.”

Take The Results Even Further

In her response to the research article, Christina Marinakis suggests one possibility for even better phrasing. Jurors may be reluctant to agree that they “have a problem.” Instead, consider a framing that makes the bias sound admirable. For example,

“Is it safe to say that you are likely to stick to your guns on this belief based on your experience?”

But Bring it Back to the “Magic Words”

Ultimately, experienced litigators might take this kind of advice with a grain of salt, knowing that the judge will be looking for specific language which often takes the form of an absolute “I cannot be fair.” In those courtrooms, the method of applying this advice will be to set the stage using the language that is most likely to get the potential juror to the point of admitting to a bias, then offering the “magic words” as a kind of confirmation. It isn’t foolproof, but it does improve your odds.

Ultimately this kind of advice can feel like a manipulation of the process. But one way of looking at it is that traditional voir dire is already manipulative: It manipulates in favor of artificially holding down expressions of bias. It is likely that some judges even do this consciously because it speeds jury selection. Innovations, like those explored in this research article, lead to greater expressions of bias. That makes it easier for advocates to do their job, and that makes a fair trial more likely.

______

Other Posts on Eliciting Expressions of Bias in Voir Dire:

______

Hamilton, M. C. & Zephyrhawke, K. (2015). Revealing Juror Bias Without Biasing Your Juror: Experimental Evidence For Best Practice Survey And Voir Dire Questions. The Jury Expert Vol. 27/No. 4 November 2015. URL: http://www.thejuryexpert.com/2015/12/revealing-juror-bias-without-biasing-your-juror-experimental-evidence-for-best-practice-survey-and-voir-dire-questions/

Image Credit: 123rf.com, used under license