By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

By all accounts available so far, deliberations in the trial of James Holmes, the gunman in the 2012 movie theater shooting in Aurora, Colorado, ended without conflict, regrets, or recriminations – at least on the part of the jury. But their deliberations didn’t end on a point of agreement either. Instead, the seven-hour deliberations concluded with the Defendant receiving the default sentence of life without the possibility of parole after jurors could not reach a unanimous verdict for either a life or a death sentence. Based on the description provided by Juror 17, the one juror speaking publicly so far, the jury reached that verdict because one juror of the 12 refused to give James Holmes the death penalty based on his mental illness. Two other jurors were uncertain while the remaining nine favored a death sentence. That result was the fruit of a capital defense jury selection strategy called “The Colorado Method,” focused on getting jurors to see a life or death sentence as a deeply personal judgment, not a matter of factual determination or group consensus. To the extent that individuals disagree, the message of the Colorado Method is to simply respect those differences. As Juror 17, who was not the holdout, explained, the group received the message that “This was an individual decision, and we had to make it based on our own moral view of what’s right and wrong.” When one juror found that he or she couldn’t sentence a mentally ill person to death, the other jurors considered that view to be “genuine” and “everyone was very cordial and respectful toward others,” Juror 17 said. “There was no arguing at all.”

The case provides a timely example of the benefits of careful jury selection. As John Ingold and Jordan Steffan of The Denver Post wrote, “The seeds that the Defense planted [in voir dire] all bloomed in the jury deliberation room.” While the Colorado Method is specific to capital defense cases, the approach carries some broader implications for litigators generally. There are other settings where one side or the other will want a juror who is willing to buck the tide of prevailing opinion. When pretrial publicity has created the perception of a foregone conclusion, or when there is a pervasive bias against the type of party you represent – say a large corporation or a bank – then parties will want jurors who are willing to stand strong and resist that prevailing opinion. In trying to find and cultivate those kinds of jurors, trial lawyers in a variety of cases might take a lesson from the Colorado Method. In this post, I’ll provide a thumbnail sketch of that method and then bridge to some implications for civil litigators beyond the capital defense jury.

What Is So Special About the ‘Colorado Method’?

Developed by Colorado public defenders about 30 years ago, the Colorado Method of capital defense jury selection is now used in venues throughout the country. The technique gained popularity following a research initiative called the Capital Jury Project (Bowers & Foglia, 2003). That project, based on interviews with hundreds of former death penalty jurors, found that many jurors misunderstood the process or served despite having a demonstrable bias in favor of death. The goals of the Colorado Method are not just to weed out the worst jurors, but also to prepare those who remain for the possibility of a life verdict. Colorado public defender David Lane described it as “essential to the verdict” in the Holmes case.

The Colorado Method, as described in a very useful and example-laden overview by Mathew Rubenstein in the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ Champion publication, is based on four principles:

1. A Single Issue: Jurors are selected based on their views on a life versus death penalty alone.

2. Life Qualify: Pro-death jurors are removed for cause if they could not seriously consider life without parole or would not need aggrevating factors in order to sentence a premeditated killer to death (this is sometimes referred to as “life qualification,” an addition to the standard “death qualification” of the jury).

3. Teach Respect: Pro-death penalty jurors are asked whether they would be able to respect the decisions of other jurors, and how they would feel bringing a life verdict out of the jury room.

4. Prioritize Strikes: Based on a seven-point spectrum ranging from excludable anti-death penalty on one end (they could not apply the death penalty on principle) to excludable pro-death penalty on the other (they would apply it automatically, with or without aggrevating factors), defense attorneys should prioritize strikes to remove the most punishment-oriented first.

More broadly, the Colorado Method frames the penalty phase as a deeply personal choice and not the product of group collaboration. The verdict represents individual moral judgment and not a community’s consensus. In sending that message, attorneys following the Colorado Method remind potential jurors that the law never requires death, and the opinions of just one juror can assign the “weight of life” to any mitigating factor. The questioning is designed to precondition jurors to the likelihood that other jurors might lean toward life, and to prevent the kind of group pressure that would lead those individuals to abandon their views.

For those possibly in the minority, opposing the death penalty in the wake of a brutal murder, the method should empower them, reinforcing the notion that the ultimate responsibility for the verdict is theirs and can’t be buried in a collective group decision. The key themes are “isolation” (the decision is an indivdual one), “insulation” (it is not to be determined, coerced, or bullied by the group, the law, or the process), and “respect” (it is the job of everyone on the jury to respect the moral choices of others. In the words of Denver defense attorney David Lane, “You teach jurors that morality-based thinking is different than fact-based thinking.” He continues, “They can have a big argument about facts, but those kinds of arguments don’t exist when you are talking about your own personal morals: One juror does not have the right to tell the other juror that your personal morals are wrong.”

Why Does It Apply Outside of a Capital Defense Context?

For capital defendants, the benefits of the Colorado Method are evident and well-supported particularly in the recent Holmes verdict. For litigators outside of that context, however, I can see a few implications worth considering.

One, Don’t Be Afraid to Go After the Single Issue Sometimes

A lawyer’s natural impulse is to try to learn about everything that matters. In the uniquely challenging and time-constrained setting of voir dire, however, focus is critical. In some cases, it might be better to avoid just learning a little about a lot of issues, and to instead learn a lot about the attitude that matters most.

Two, Use Scales

One strength of the Colorado Method is its advice to categorize jurors based on the type and strength of their attitudes on life and death (see Rubenstein, p. 1-2). The precision in assigning a numeric weight will never be perfect, but will give you a useful starting point on how to prioritize your strikes.

Three, Ask For Their Thoughts, Not Their Promises

Using voir dire to precondition and precommit your panel is generally not the best use of time: They haven’t seen the evidence and don’t know what they’ll do in response to specific facts and instructions. Instead of asking for promises, ask open-ended questions that are designed to gain information. Only after you’ve made the choice to try to remove a juror for cause should you shift to the ‘record-building’ phase by asking leading closed-ended questions.

The capital defense jury selection setting is obviously unique: In that context, counsel is often trying to discourage a collective outcome and not encourage one. But still, the Colorado Method is a good example of a perspective that looks at the dynamics of the jury, seeing the verdict as a process and not just a product of static attitudes. The themes of juror independence and strength in the context of that process speak to other case scenarios as well.

______

Other Posts on Jury’s Decision Making Process:

- See the Process and Not Just the Product in Deliberation

- No Blank Slate (Part 2): In Closing, Treat Your Jurors as Instrumental Arguers

- Determine Whether Your Jurors Are Driven by Process or by Verdict

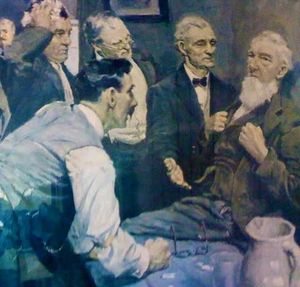

Picture credit: Detail of H.M. Brett’s “The Hung Jury,” public domain.