By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

If you’re going to lose your case, how will you lose? What is the most likely scenario that would have the jurors going in the other direction? That question lies at the heart of a theme approach that I’d like to demonstrate via a short video (below) from a recent conference. A colleague of mine, New York consultant Suann Ingle, calls this approach the “Pre-Mortem” in the sense that asking the “How do I lose?” question can help you win by allowing you to build your best response to that question into your central message. Sure, it is always good to think positive…to an extent. But a theme that speaks to those positives without giving attention to the worst case scenario risks preaching to the choir. That isn’t the best role for a theme. Instead, an effective central message for your case should target the higher risk jurors. Based on that “Pre-Mortem,” it should make it as difficult as possible for those jurors to take a route that leads them to vote against your case.

At a conference for the American Society of Trial Consultants earlier this month in Asheville, North Carolina, I joined a panel to explore how different consultants would address the same fact pattern. I shared the stage with three of the most experienced consultants in the country: Pete Rowland (of Litigation Insights), Theresa Zagnoli (of Zagnoli McEvoy Foley), and Charli Morris (of Charlotte Morris Litigation & Communication Consulting). I believe that the ASTC will be hosting the video from the whole panel. but in the meantime, I wanted to use my own introduction to illustrate this idea of targeting your worst audience through your theme. This post includes a brief overview of the fact pattern, a video recording of my five-minute introduction, and then a transcript where I include an explanation of why I made the choices I made in the introduction.

The Fact Pattern: Jackson v. Newland

We have used this fact pattern in a few instances before, including our visual persuasion study. It is a fictional account of a young baseball pitcher injured after being struck by a batted ball. Here are the vitals:

- 16-year-old high school baseball pitcher, struck and brain injured by a ball batted from a Newland “Series 7 Accelerator” bat – an aluminum alloy bat.

- Plaintiff claims Newland manipulated the bat design and duped the bat standards test to allow greater exit speed for the ball. That increase in speed causes a pitcher to not have enough reaction time to avoid the ball.

- Plaintiff claims that Newland advertised the Accelerator as a faster bat, and that it tested faster than other bats on the market.

- Defense claims that the bat passed all relevant tests, and was not manipulated.

- Defense also claims that any bat, with the right hitter, would have produced the same injury.

For the theme exercise, I drew from our previous research indicating that defense is likely to win this case around 65 percent of the time. This is due to a couple of important barriers: One, jurors assume that the plaintiff’s case is all about sympathy, and two, jurors consider the risk of injury to be just one of the common risks of baseball. So, seeing that as the challenge, here is an introduction designed to address that risk.

The Video: A Five-Minute Introduction

(Those of you receiving this post by subscription, I know you can’t see the video above, but you can access it by following this link).

The Analysis:

[Note: The transcript appears in blue, while my comments are in black]

This case is about a pitch, but not about a pitch delivered from the middle of a baseball diamond.

From the outset, I wanted to distance the case from the Plaintiff himself to prevent jurors from believing that it is a sympathy appeal about a young boy.

This case is about a pitch delivered from inside a corporate product development lab. A pitch at the market, a pitch to see if they could get past a flawed test, and ultimately a pitch at you.

I also adopted this idea of a “pitch” with both its baseball and marketing connotations. The later is important, since we learned that jurors avoid sympathy because they don’t want to feel manipulated. So the theme in this case emphasizes that it is the Defendant company in this case who is doing the manipulation.

And the goals of this pitch came from Newland asking themselves a few questions: What if we designed a bat with greater pop or exit speed of the ball off the bat? What if we gained greater market share by advertising this greater pop, this advantage over other bats? What if we did both of those while still somehow getting the bat past the test that is designed to place a cap, for safety’s sake, on exit speed off of the bat? And what if, when injuries inevitably occur, we’re able to say that that’s part of the normal harms of baseball?

Note that the entire focus is on the company. I wanted to keep Newland at the center of the story knowing that the higher risk jurors react negatively to any early focus on the plaintiff (since this would confirm their belief that the case is about sympathy) and emphasize the company’s power and choices.

So here is the windup for that pitch: Newland and their top scientist, Dr. Carl Weatherspoon, try to load as much energy into this bat. They do that by taking the weight of the bat, set by regulation at 30 ounces, and moving as much of that weight as possible down into the handle and leaving as little weight as possible in the barrel or the hitting surface of the bat. Now that does two things. Number one, it dramatically increases the swing speed of the bat. And number two, it maximizes what’s called the trampoline effect – when that thin wall of the bat barrel bends in to receive the energy of the ball and then springs back to release that energy back into the hit.

We also knew from the pretrial research that the Defense had a good argument that, however good or bad the test is, they passed it and that’s all they need to do. To address that, the emphasis is on their manipulation, or “windup” of that test.

Now that is the windup, and here’s the pitch. They still need to get this bat past the test — the ball exit speed ratio, BESR test. Now it sounds fancy, but it’s actually pretty dated. It’s a perfectly fine test for back when bats were uniform and made out of aluminum, but wholly inadequate for modern bats made out of aluminum alloy and highly engineered. The worst fact about this test is that it’s done on a stationary bat. That’s right – a bat that’s not moving. They essentially fire a ball at the bat and then record how fast the ball bounces off. So, it doesn’t account for the swing speed. It doesn’t account for the part of the bat that Newland manipulated. And Newland was able to get their pitch past a nearly blind umpire.

I thought that this level of detail, atypical for an introduction, was necessary just based on the amount of faith that we saw defense-oriented jurors placing in the test. If I was going to get anywhere with these jurors, I knew that I needed to introduce some early skepticism of this test. That meant explaining how it works, as well as what it leaves out.

And it wasn’t a wild pitch either, it went exactly where they intended. You will see evidence that Newland knew that they were exploiting the flaws in this test. You’ll see internal company documents, including one from Dr. Weatherspoon that says, “We see opportunities to move forward and design around the restriction.” And Newland was proud of that advantage. You’ll see trade journal publications that say, “This bat hits with greater pop than other bats.” Even one ad that went so far as to say, “Watch out pitcher.” Watch out pitcher.

We knew that the naturally pro-defense jurors simply would not hold the company responsible for an inadvertant injury. So we had to make the outcome as intentional as possible. That is why the introduction has emphasized the company’s choices: external and internal communications that show the company’s knowledge.

But here’s the thing — this bat, the redesign, the manipulation by Newland — deprived the pitcher and every other player on that diamond of the ability to watch out. You know, you’ll see the science, but there’s a minimum reaction time that the eye and the brain needs to see an object and get out of the way or catch it. It’s 400 milliseconds — a little less than half a second. And this manipulation, the tests show, increases the speed and brings the reaction time below that threshold. So the pitcher cannot watch out.

The issue of reaction time is technical, but essential in getting skeptical jurors to shift their attention from the players on the field to the company. Also emphasizing that the case is based in science, helps these jurors to get past the perception that the Plaintiff is grounding their case in a sad outcome and appealing to sympathy.

And so with that knowledge and that manipulation, it’s not a question of whether someone will be hurt, it’s a question of who and when and where and how many. And the family that is bringing this case is one example of one consequence of Newland’s decision to try and pitch past a flawed test, and they did by design.

The attempt here is to downplay this individual Plaintiff (who isn’t even named in the introduction) and make the point that the case is about the safety of all players. This approach also tracks with the Reptile perspective by encouraging jurors to see the case through a frame that carries relevance to themselves and their loved ones.

And they’re going to try to pitch past you as well. Now, our expectation of the pitch for you is going to be that this is a case about sympathy. This is a case about the inherent risk of sport and youth. Or that this is a case about baseball. Don’t swing at any of those. None of those are true. This is not a case about a tragic pitch from the center of a baseball diamond. This is a case about a tragic and irresponsible decision from a corporate product development lab. And this is a case about a dangerous and irresponsible pitch being made by Newland, still today here in this courtroom.

As a guard against defense-oriented jurors’ feelings that this Plaintiff, and plaintiffs generally, try to manipulate, the emphasis here is that it is the defense who will be trying to manipulate you by oversimplifying the case and distracting you from their own choices.

This approach is just one of many, and hopefully readers will be able to see how other consultants address the same case study, including the response from the defense. But I believe the same principle applies to both sides. The temptation is to focus on your strengths and to speak to your most favorable audience. But the more effective use of those precious introductory minutes is to aim at a worst case by targeting your theme toward the factors that would make you lose.

______

Other Posts on Theme:

- Make Your Trial Theme Cinematic…Or At Least Memorable

- Go for Sticky Theme Over Catchy Phrase

- Beware the Anti-Theme

- Right-Size Your Message in Trial

______

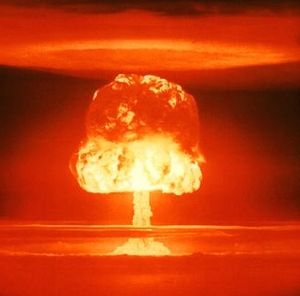

Photo Credit: rOckchuck, Flickr Creative Commons