By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

President Trump has just announced the third version of his ban on travel to the U.S. by residents from specific countries. This time the ban includes the unlikely traveler from North Korea and some Venezuelan officials, but this third version is still recognizable as his ‘Muslim travel ban,’ the campaign promise that, in practice, has led to widespread public resistance and continuing constitutional challenges. But it certainly has its supporters as well. In fact, the persistence of this issue serves as a reminder of the fact that Trump isn’t alone in his tendency to distrust individuals from the Middle East, or those who are Muslim. The full extent of that bias might be a little surprising, particularly to those of us who live in the liberal urban and like-minded enclaves, or those who work in law and might be tempted to take civil rights for granted. Outside of those contexts, anti-Islamic bias is still very high.

That bias can matter in the courtroom. If you have a party or a witness who identifies as Muslim, or wears a hijab or other religious identifiers, if there is something about their outward appearance that seems Middle Eastern, or if they practice a faith that is often mistaken for Muslim – like Sikhs, Middle Eastern Christians, or even orthodox Jews — that party or witness could be perceived as a threatening ‘other,’ and could end up on the receiving end of that bias. Even when discrimination isn’t the legal claim, it may be the reality coming from the jury box. In this post, I will take a look at a fairly recent survey showing the extent of anti-Muslim bias, and share some areas of questioning that serve to uncover that bias in jury selection.

The Level of Fear

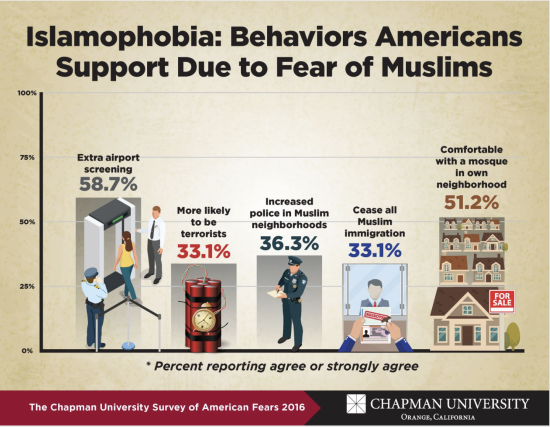

You don’t have to follow the news on the travel ban in order to know that a large proportion of the American public distrusts muslims. Yet the level of that bias might still be surprising. Based on the 2016 Chapman University Survey of American Fears, fully 44 percent of the population admits to distrust for muslims, higher than atheists (37 percent) or law enforcement (22 percent). Only the generic category of “strangers” earned higher levels of distrust from the population.

That level of distrust translates into a number of specific fears.

Even when a case doesn’t involve terrorism, security, the police, immigration, or mosque-siting, it is likely that these attitudes will color the credibility assessment of someone who is Muslim or perceived to be so.

As you would expect, however, these attitudes do not distribute evenly across the country. While comparisons between American regions (e.g., Northeast versus South) did not turn out to be significant predictors, several other demographic factors did. In all, anti-Islamic Americans are somewhat more likely to be white, older, Republican, less educated, male, and rural residents.

Focusing on Anti-Islamic Bias in Voir Dire

If you do find yourself in the position of having to persuade someone who may be biased against your client or witness, then the best recourse is to focus on the courtroom as a special setting that calls for a particular temporary identity, and gives jurors a reason to try to step outside of their ordinary biases for the duration of the trial. But, on the whole, it is better to focus on uncovering and challenging these biases in voir dire rather than trying to persuade the biased during trial.

To get at that bias, you are best off using a questionnaire, ideally one that jurors fill out at home. There is evidence that, particularly on sensitive matters, individuals might be reluctant to speak of aloud, the perceived privacy of a paper questionnaire leads to greater levels of candor. The questionnaire answers, ideally analyzed outside of court, can then serve as a springboard for follow-up questions and for cause challenges.

If you are developing a questionnaire on anti-Islamic bias, one useful resource is a piece by Diane Wiley in The Jury Expert. The article includes 28 questions that this well-regarded consultant from the National Jury Project has used. The areas of questioning that I would emphasize the most are as follows:

What kinds of contacts have you had with Muslims, people of Arab descent, or others from the Middle East?

Have your experiences with these individuals been positive, negative, or mixed?

How significant a problem do you think prejudice against Arabs and Muslims is in this country today?

Do you believe that Muslims, people of Arab descent, or others from the Middle East are more or less likely to do the following:

Be honest in business?

Engage in acts of violence or terror?

Call for restrictions on personal freedom in speech or religion?

What are your reactions to recent controversies in the news, for example, President Trump’s restrictions on travel from several majority-Muslim countries?

Of course, these questions will also vary according to your case and your venue. In evaluating the venue, it is important to understand what the local awareness has been: Has the issue been in the news? Are neighborhoods changing due to Muslim immigration?

The continuing debate over the President’s travel ban ensures that the issue isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, and anti-Islamic attitudes are likely to polarize even further. As with all biases, better to know than to speculate.

______

Other Posts on Group:

- Account for Disinhibition of Bias

- Don’t Expect Reliable Juror Differences Based on National Origin

- Instruct Jurors on Unconscious Bias

______

Photo credit: Lorie Shaull, Flickr Creative Commons, Edited