By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm:

Rushing into the courtroom, late in returning from a break, the lawyer stood before the already seated jury, red-faced, but with a self-deprecating smile. “Ladies and gentlemen, this is what every lawyer fears, and I’m truly…mortified to have kept you waiting.” And the jury responded not with irritation, but with warm smiles and chuckles. Why? Not because they enjoyed wasting their time (note: jurors don’t), but because this lawyer had just humanized himself by sharing an unplanned moment of sincere embarrassment.

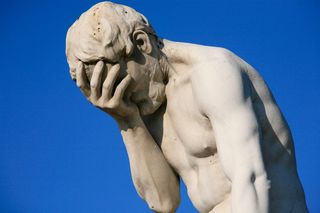

So embarrassment is persuasive? Yes, according to a recent study (Feinberg, Willer & Keltner, 2011), people who are easily embarrassed and willing to show that, are more generous, more trustworthy, and in fact, more trusted. The key ingredient is humility, which can be refreshing to a jury expecting attorneys to convey distance, superiority, and arrogance instead. This post takes a look at the research as it relates to humbling courtroom moments, and suggests a couple of cardinal rules for humanizing yourself in front of a judge or a jury.

The Research:

Mathew Feinberg, Robb Willer and Dacher Keltner published an article in the current Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, “Flustered and Faithful: Embarrassment as a Signal of Prosociality.” Prosociality in this case, means an evident concern for others, and those who care enough to be embarrassed over modest mistakes apparently earn an audience’s trust. The researchers conducted a number of experiments, including one in which an actor conveys either pride or embarrassment in response to a situation, and the embarrassed response ends up being more winning. In multiple studies covering a range of situations using both real and simulated embarrassment, study participants viewed the embarrassed response as more pro-social.

According to lead author Matthew Feinberg, a doctoral student in psychology at UC Berkeley, the individual willing to show honest embarrassment is more trusted because they’re willing to let down their guard and show that they care about the situation and the audience. “You want to affiliate with them more,” he said, “you feel comfortable trusting them.”

Implications:

Before you take this research to heart and decide to stage a trip on your way to the lectern, or arrange to strategically leave your fly open at the start of oral argument, there are a few important considerations in trial. First, it is important to remember that a courtroom is an unusual situation. Even when not in session, walking into a courtroom is a little like walking into church. It is quiet and reverential, and there are narrow parameters on what you can say and do. In that context, it is much harder to break the tension, and at the same time, it is much more of a relief when you actually do. So remember a couple of cardinal rules for how you humanize yourself in court.

1. The key word is unplanned. Accidentally showing the jury a picture of your family on your computer desktop – even if it is truly accidental – could be seen as intentional, and nothing is less humble than an intended ploy to make oneself appear more humble. So, while it helps to keep your eyes open for a chance to lighten the mood or to show your feet of clay, it almost never works when you plan it. Nine times out of ten, “jokes” will fall flat, and whatever humor there is in court will emerge spontaneously.

2. The best humor is self-deprecating. I was once in court when an expert witness in the middle of cross-examination mishandled a notebook and ended up dumping a full glass of water onto his notes and his lap. There was stunned silence, followed by a court officer rushing in with paper towels. While the witness himself probably could have broken the tension with a wry remark (“I suppose now you’re going to say my analysis is all wet…”), he didn’t, and the important thing is that no one else could have. It is a good rule of thumb that courthouse humor should be at your own expense, not anyone else’s.

Perhaps the most positive message, however, is that those in court living in fear of a foible, flub, or pratfall should rest a little easier. A mistake followed by a natural and possibly humorous moment of embarrassment doesn’t spell the end of the line for your credibility, but instead just provides a small opportunity to show that you’re human after all.

______

Related Posts:

- Remember in Court, If You’re in View, Then You’re on Stage

- Avoid Condescension and Other Sins of Legal Argument: Know Your ‘Second Persona’

- Experts: Don’t Cross The Line Between Confidence and Arrogance

____

Feinberg M, Willer R, & Keltner D (2011). Flustered and faithful: Embarrassment as a signal of prosociality. Journal of personality and social psychologyPMID: 21928915

Feinberg M, Willer R, & Keltner D (2011). Flustered and faithful: Embarrassment as a signal of prosociality. Journal of personality and social psychologyPMID: 21928915

Photo Credit: Alex E. Proimos, Flickr Creative Commons