By Dr. Ken Broda Bahm

Earlier this Spring, a courthouse in Jackson Mississippi was actually invaded by snakes. That story might have made some in the plaintiff’s bar smile a bit, since in their view, Reptiles have been invading American courtrooms across the country for a few years now. Reptile: The 2009 Manual of the Plaintiff’s Revolution by David Ball and Don Keenan, as well as associated books, DVDs and training seminars, have significantly influenced plaintiffs’ methods of trying cases, and the philosophy currently claims close to $5 billion in associated verdicts. Adherents believe that by framing legal claims as basic appeals to community and personal safety, they are able to wake up jurors’ reptilian minds and motivate verdicts in their favor. As I’ve written before, there is reason to believe the theory rests on a dubious foundation (the largely discredited belief in a reptilian brain governing the rest of our decision making), but that it works nonetheless (because it encourages persuaders to put motivation front and center).

Earlier this Spring, a courthouse in Jackson Mississippi was actually invaded by snakes. That story might have made some in the plaintiff’s bar smile a bit, since in their view, Reptiles have been invading American courtrooms across the country for a few years now. Reptile: The 2009 Manual of the Plaintiff’s Revolution by David Ball and Don Keenan, as well as associated books, DVDs and training seminars, have significantly influenced plaintiffs’ methods of trying cases, and the philosophy currently claims close to $5 billion in associated verdicts. Adherents believe that by framing legal claims as basic appeals to community and personal safety, they are able to wake up jurors’ reptilian minds and motivate verdicts in their favor. As I’ve written before, there is reason to believe the theory rests on a dubious foundation (the largely discredited belief in a reptilian brain governing the rest of our decision making), but that it works nonetheless (because it encourages persuaders to put motivation front and center).

While not exclusive to the field of medical malpractice, the Reptile and the earlier Rules of the Road work by Rick Friedman both focus strongly on coaching plaintiffs to win these and similar claims related to safety. For defendants generally, I think the theory is best approached by stripping away some of the brain lore used to market the approach, recognizing that without that the Reptile is still a formidable means of legal persuasion, and then finding parallel ways to appeal to jurors’ basic motivations. In this post, I want to take a closer look at the perspective, focusing on one element that is a particular vulnerability to the theory in a medical context: the safety rule

Safety Rules: The Soft Underbelly of the Reptilian Perspective

According to both the Reptile and the Rules of the Road views, the key to the plaintiff’s ability to persuade is to ground the case, not in a legal standard of care, but in a “safety rule,” or a commonsense principle jurors can immediately understand and apply to other contexts. In the formula Ball and Keenan advocate, “Safety Rule + Danger = Reptile” means that once the advocate is able to identify such a rule, and show fact finders the danger to themselves and the community when it’s violated, then they’ve awakened those jurors’ reptile brains, motivating them to equate justice in this case with their own security.

In other words, the safety rule might be that doctors should do nothing without a patient’s or family’s agreement. The danger lies in doctors practicing in ways that take away our freedom and might miss hidden dangers. When jurors see both, then they’ll act, not in defense of a legal standard of care or abstract notion of “informed consent” but in order to prevent the doctor-defendant, and others like him, from threatening the safety of patients like the jurors and their loved ones. So the act of identifying a safety rule is key to the theory. Even setting aside the notion of a primitive reptilian brain, the articulation of a simple and widely applicable rule is what frames the conflict and motivates the jury, encouraging them to view the dispute in personal and community terms.

Not just any safety rule works. To really “awaken the reptile,” the rule needs to have the six qualities identified below. These rules about rules are not arbitrary, but help get plaintiffs over the barriers to jurors seeing themselves and their verdict as key to promoting safety and removing danger.

What the Plaintiff Wants (and What Medical Reality Often Refutes)

Underlying all six elements of a safety rule is a black and white view of the medical world. But the advantage for medical defendants is that the real world of treatment and care typically isn’t black and white, but is instead situational and highly dependent on a particular patient’s circumstances. In resisting plaintiff’s attempt to distill it down to one pithy rule, medical defendants will generally have reality on their side. This sets up a conflict that has existed prior to and aside from this Reptile approach, but has been magnified by it: As plaintiffs’ attorneys push for a black and white worldview, defendants push back with a realistic appraisal of shades of gray.

The “umbrella rule,” or the formulation with the widest possible application is that “doctors are never allowed to needlessly endanger their patients.” That rule will contain a variant for each particular case, and there are six criteria that, according to Ball and Keenan, will determine whether that safety rule is effective or not. Blocking the overly simplistic rule thwarts the Reptile approach by minimizing the perception of personal and community danger, bringing the focus to what the case should be about: a particular plaintiff’s treatment by a particular physician.

The response on each of these six elements should inform the ways medical defendants prepare fact and expert witnesses, conduct voir dire, and create openings and closings. Each effort to deny a safety rule in your own case can be part of your message at trial.

1. The Safety Rule Must Prevent Danger

Of course, nothing is able to literally and fully “prevent” danger. Teach your jury that physicians are instead trying to lessen its impact or control its course. The reality is that medical care often involves swapping one danger for another in an imperfect effort to make the patient better off. For example, you prescribe a drug with known side effects in order to treat a condition that is, probably, worse than the side effects. This means that the line from the Hippocratic Oath to “first, do no harm” isn’t literally true. Excising tissue in a surgery, for example, is doing harm, but a lesser harm than doing nothing. This, of course, is something that doctors, claims representatives, and defense attorneys understand intuitively. Jurors may resist the message, wanting to believe that physicians can guarantee safety. With a little explanation, however, they can realistically set that notion aside.

2. The Safety Rule Must Protect People in a Wide Variety of Situations, Not Just Someone in the Plaintiff’s Position

Key to the Reptile’s advice is to encourage jurors to abstract beyond the particular patient-plaintiff and to view the rule as broadly applicable and personally relevant. But chances are, patients’ situations are not interchangeable, and there is no easy cut-and-paste set of rules that apply to all. Doctors have the job of treating the patient, and the more jurors understand that this is highly particular — patient and situation specific — the better they’ll be able to resist the general safety rule.

3. The Safety Rule Must Be in Clear English

Of course, there is nothing wrong with clear English, but making something perfectly clear in a medical context should never require softening, generalizing, or leaving out key medical distinctions. A dumbed-down principle can be a less accurate principle. Complexity for its own sake is the defendant’s enemy, and can be rightly seen as obfuscation. But realistic complexity — factors and distinctions that are critical to patient care and can be patiently and accurately taught to the jury — is defendant’s friend.

4. The Safety Rule Must Explicitly State What a Person Must or Must Not Do.

The key language here is “must” and “must not.” There is no room in a Reptile perspecitve for “typically,” “probably,” or “in most cases.” It has to be an imperative: “If the doctor sees X, she must do Y.” Certainly, there are some parallels to this absolute and linear decision-making in a medical context, but there are also plenty of situations where it isn’t a “must” or a “must not,” it is a realistic “it depends.” Help jurors understand that by explaining and supporting all of the factors that go into that choice. Using a graphic showing a more complicated decision-tree, for example, can truthfully undermine any plaintiff’s rule that assumes an “if A, then B” style of thinking.

5. The Safety Rule Must Be Practical and Easy for Someone in the Defendant’s Position to Have Followed.

It is often practical and easy in hindsight: If only Dr. Smith had ordered that biopsy, or if only Dr. Jones had transferred the patient earlier. But the question is never what would have provided better care in retrospect, it is always whether appropriate care was delivered based on what was known and believed at the time. Could the physician have ordered a different test at an earlier time? Of course, that is going to be both practical and easy. But did the physician have solid reasons at the time to have ordered that test? That is a different question. Of course, getting jurors past this psychological preference for hindsight can be a challenging task, but not an insurmountable one. You can encourage jurors to adapt a hindsight-resistant mindset by using a timeline to walk through the story based on what was known at the time, and by focusing on the multiplicity of treatment options, not just the one obvious choice that could have been made in hindsight.

6. The Safety Rule Must Be One That the Defendant Will Either Agree With or Reveal Him or Herself as Stupid, Careless, or Dishonest for Disagreeing With

This final rule really sums up the mindset: You either agree with a simplistic rule, or you are stupid, careless or dishonest. To fight back, you need to mount an educational offensive that frames the choice as something other than that. For example, craft your own safety rule that is simple, yet honest: a principle that jurors can understand and that the doctor followed in this case. If the true rule is a little more complicated than the plaintiff’s proffered rule, then make jurors proud of the extra effort it takes for them to get it: They aren’t taking the easy route, they’re taking the accurate route.

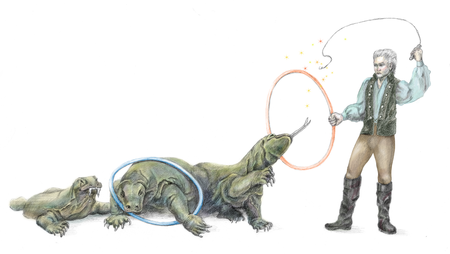

Plaintiffs Are Pandas and Defendants Are Seals

Since I began this post talking about snakes, let’s end it by talking about some other animals. Noting the responses I outline above to the six criteria for a successful safety rule, it is clear that at every point, the Reptile practitioners are aiming for the simplicity and comfort of an absolute and cut-and-dried formula for medical care. It is so wedded to the black and white that it could have been called “Panda” rather than “Reptile.” Defendants, on the other hand, are often realistically wrapped in all shades of gray — like seals. In practical terms, plaintiffs are often the ones saying, “It’s simple, it’s clear, it’s obvious” while defendants are responding, “Not so fast. There’s more to it than that.”

Psychology can have a preference for the black and white and for low effort thinking. That is why the Reptile approach works. But reality is often gray, especially in a medical context. That is a big advantage, and defendants shouldn’t hesitate to use it. The panda can be appealing, but better education can seal the deal.

______

Other Posts Related to the Reptile Approach:

______

Original Illustration: Pamela Miller, Persuasion Strategies